Cao Zhen

caozhen0806@126.com

A HUNDRED ink paintings by legendary master Zhang Daqian are being showcased in the Shenzhen Museum at Civic Center, offering a glimpse into the artistic life of the Chinese painter and demonstrating his status as a truly global artist.

Zhang (1899-1983), also spelled Chang Dai-chien, was ranked by market database Artprice as the best-selling artist in auctions in 2011, overtaking his one-time acquaintance Pablo Picasso. In May 2013, one of his “Lotus” paintings created in 1947 fetched US$10.4 million at a Christie’s auction in Hong Kong.

Zhang is renowned for his artistic versatility. He portrayed ladies, landscapes, flowers and figures on Dunhuang frescos, as well as copied ancient Chinese masterpieces. The exhibition charts his artistic development from the 1930s to the early 1980s, showing his talents in gongbi (traditional Chinese realistic painting style), splash-ink and splash-color painting techniques.

The exhibited items are provided by the Museum of History in Taipei, Jilin Provincial Museum in Changchun, Sichuan Provincial Museum in Chengdu and Shenzhen Museum. The exhibition, commemorating the 30th anniversary of Zhang’s death, will continue its tour in Taipei, Changchun and Chengdu after concluding in Shenzhen on March 2.

Zhang’s career as an artist began in his early years. Born into a rich and educated family in Neijiang, Sichuan Province, he was taught to paint by his mother at 9 years old. In 1917, he was accompanied by his elder brother Zhang Shanzi (an artist famous for his tiger paintings) to study textile dyeing in Kyoto, Japan. After he returned to Shanghai in 1919, he received formal painting and calligraphy instruction under two Shanghai artists, Zeng Xi and Li Ruiqing.

Through his association with these teachers, Zhang had the opportunity to study works by ancient masters in detail. Zhang’s favorite artist, Shi Tao (1642-1707), was a great influence on him. Zhang took great inspiration from Shi as well as other painters of the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, including Tang Yin (1470-1524) and Chen Hongshou (1599-1652). At the Shenzhen exhibition, viewers can admire a 3.45x1.34-meter ink painting Zhang copied from Shi in 1934.

“Zhang’s copies are difficult to detect because of his virtuosity and scrupulous attention to the materials he used,” said Ba Dong, chief of Research Division of Taipei’s Museum of History, at a lecture in Shenzhen on Dec. 28. “He studied paper, ink, brushes, pigments, seals, seal paste and scroll mountings in exacting detail. Many of his copies successfully deceived overseas collectors and museums.”

Zhang’s prodigious ability to mimic ancient images can also be found in his paintings of Dunhuang frescos. In 1940 Zhang led a group of artists to the Dunhuang areas in Northwest China’s Gansu Province to copy Buddhist frescos inside numerous caves. In less than three years, the group completed 276 paintings, and the experience left Zhang with a repository of religious imagery. The caves in Dunhuang are particularly noted for their Buddhist art, spanning from the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534) to the Five Dynasties (907-960). At the Shenzhen exhibition, viewers can not only admire Zhang’s portraits of the benign Guanyin bodhisattva but also the awe-inspiring Yaksa, a god who protects the righteous.

Zhang’s gongbi technique, consisting of highly detailed brushstrokes in traditional Chinese painting, is well reflected in his portraits of traditional women. Gongbi requires a careful realistic technique that sets in details very precisely. In the Tang (618-907) and Song (960-1279) dynasties, only the wealthy could afford gongbi artists and this style of art was accomplished in imperial palaces or private homes. Zhang’s meticulous brushwork in portraits, flowers and birds is clearly inspired by his study of the ancient masters and Dunhuang cave art.

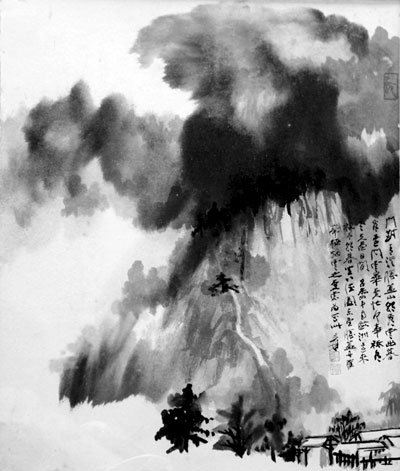

As a versatile artist, Zhang developed his splash-color style in the late 1950s due to his deteriorating eyesight. The artist fused the splash-ink technique of Tang Dynasty painter Wang Mo (also known as Wang Qia) with Western Impressionism effects. This was a departure from his traditional-style exquisite brushwork. It gave him the freedom to splash ink or color on rice paper and relied on random chance to express the interplay of paper and ink, sometimes with little brushwork. In his landscapes with bulky black, green or blue splashes, he didn’t reproduce the exact appearance of nature but rather grasped an emotion or atmosphere and captured the rhythm of nature. Zhang’s splash-color paintings are highly coveted at international auctions.

During his lifetime, Zhang was invited to hold exhibitions in cities around the world, including London, Paris, New Delhi, Boston and New York. He also painted mountains and lakes of Europe and South America in the splash-ink style. In 1956, when holding an exhibition in France, he met Picasso, which was viewed as a summit between the preeminent masters of Eastern and Western art.

Zhang’s artistic legacy is immense and complicated. Living a life of travel and wartime exile, Zhang was a highly social personality who enjoyed his fame and artistic expression. Two Mandarin lectures on his life and paintings will be held Jan. 11 and Feb. 22 at 2 p.m. at Shenzhen Museum.

Dates: Until March 2

Hours: 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Closed Mondays

Venue: Shenzhen Museum, Civic Center, Futian District (福田区市民中心深圳博物馆新馆)

Metro: Shekou or Longhua Line, Civic Center Station (市民中心站), Exit B

|