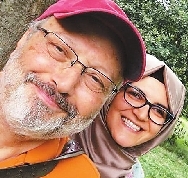

FOR decades, Jamal Khashoggi was one of the most powerful voices in Middle East journalism. Born to a prominent Saudi family, he spent much of his career straddling a line between the media world and the kingdom’s establishment, with unrivalled access to princes and Western diplomats. But increasingly he became a thorn in the side of the new ruling elite surrounding Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman as he wrote of his mounting concerns about the direction the world’s top oil exporter was taking under the young heir apparent. The Washington Post contributor has called for public debate and defended both freedom of expression and Islamist groups. Khashoggi, 60, went into self-imposed exile in the United States in 2017 after falling from grace with the crown prince. He described a new Saudi era of “fear, intimidation, arrests and public shaming” in an article published in the Post that year. In a March 6 Guardian editorial co-authored with Robert Lacey, Khashoggi wrote: “For his domestic reform program, the crown prince deserves praise. But at the same time, the brash and abrasive young innovator has not encouraged or permitted any popular debate” on the changes. “He appears to be moving the country from old-time religious extremism to his own ‘You-must-accept-my-reform’ extremism, without any consultation — accompanied by arrests and the disappearance of his critics.” After two weeks of denials, Riyadh on Saturday finally acknowledged that Khashoggi had died in the kingdom’s consulate in Istanbul after the journalist had entered the diplomatic mission Oct. 2. Saudi authorities said he was killed in a fight with Saudi officials, claims treated with widespread skepticism. Turkish officials have said Khashoggi was killed by a 15-man Saudi hit team that flew into Istanbul and dismembered the journalist’s body. “He was worried about being targeted, big time,” said a friend who met him three weeks before his disappearance. The friend, who described the journalist as a father figure, said being away from the kingdom hit Khashoggi hard and he struggled with loneliness and homesickness. Born in 1958, Khashoggi grew up in the holy city of Medina and studied at Indiana State University in the United States before returning to the kingdom to work as a journalist in the 1980s. His grandfather was doctor to Ibn Saud, the founder and first king of Saudi Arabia. He gained recognition for his coverage of the Afghan war — including an interview with Osama bin Laden, the al-Qaida leader — and the first Gulf war before he was named deputy editor-in-chief for the English-language daily Arab News. One of the region’s highest-profile journalists, Khashoggi was seen as someone familiar with the thinking of Saudi leaders, but his ties to power in the kingdom fluctuated, and his career as one of the country’s top journalists was punctuated with a series of controversies. In 2003, Khashoggi was sacked less than two months after being appointed editor-in-chief of al-Watan daily, following critical coverage of the kingdom’s then-feared religious police. He then worked as an adviser to Prince Turki al-Faisal, the former Saudi intelligence chief, before returning as editor of al-Watan in 2007. Khashoggi’s second stint lasted for three years, until he resigned under pressure after the newspaper published an op-ed that criticized Salafism — a strict interpretation of Sunni Islam. He was soon named managing director for a news television channel by tycoon Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal, but the channel was shut down on its first day on air after hosting a Bahraini opposition figure. Khashoggi was also a frequent commentator who appeared on international and regional television channels and has gained a wide following with his appearances on Arab satellite television networks. “Jamal was — or, as we hope, is — a committed, courageous journalist,” The Washington Post’s editorial page editor Fred Hiatt said in a statement. “He writes out of a sense of love for his country and deep faith in human dignity and freedom.” And he was a mentor to many young Saudi and Arab journalists who, even though they may have disagreed with his opinions, always respected his experience and sought his advice about their work and careers. As a series of popular uprisings shook the Arab world in 2011, Khashoggi was criticized in the kingdom for expressing sympathy with Islamist groups that reached power such as the Muslim Brotherhood, a group he had flirted with in his youth. That link became increasingly problematic after the Saudi Government classified the group as a terrorist organization. In November 2016 when Saudi leaders were seeking to cement ties with Donald Trump, officials banned Khashoggi from writing and tweeting after he criticized the then president-elect during a discussion panel organized by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. He was allowed to resume writing his weekly column in the pan-Arab daily al-Hayat in August 2017 but that return proved shortlived. Prince Khaled bin Sultan, the newspaper owner, suspended him after he defended the Muslim Brotherhood in a series of tweets. Khashoggi fled the country in September 2017, months after Prince Mohammed was appointed heir to the throne and amid a campaign that saw dozens of dissidents arrested, including intellectuals and Islamic preachers. After he left the country, pro-government writers and commentators often labelled him a traitor for criticizing the crown prince and his policies. “I have left my home, my family and my job, and I am raising my voice,” Khashoggi wrote last September. “To do otherwise would betray those who languish in prison. I can speak when so many cannot.” Two months later, he wrote that Prince Mohammed was dispensing “selective justice” and claimed there was “complete intolerance for even mild criticism” of the crown prince. “The crackdown on even the most constructive criticism — the demand for complete loyalty with a significant ‘or else’ — remains a serious challenge to the crown prince’s desire to be seen as a modern, enlightened leader,” He wrote in The Washington Post on Nov. 5. Khashoggi has also criticized Saudi Arabia’s role in Yemen, where Riyadh leads a military coalition fighting alongside the government in its war with Iran-backed rebels. The writer opposes a Saudi-led boycott of Qatar, a tiny Gulf emirate that has found itself isolated over its allegedly close ties to extremist groups and Iran. Khashoggi met Hatice Cengiz, a 36-year-old Turkish researcher with a focus on the Gulf, at a conference last May. The two kept in touch, fell in love and decided to marry. On Oct. 2, Khashoggi went to the Saudi consulate in Istanbul to retrieve papers of divorce from a previous marriage. Khashoggi did this knowing it was a risk. Khashoggi told Cengiz to call an adviser to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan if he did not return. “Love and women, they make you do crazy things,” a friend said. “He needed someone. He loved Hatice. He wanted to get out of the consulate to celebrate with her.” Speaking to The Washington Post a week after his disappearance, Cengiz said: “As his fiancee, as someone close to Jamal and in love with Jamal, I am waiting for information from my government about what has happened to him.” Khashoggi’s death has triggered Saudi Arabia’s biggest diplomatic rift with the West since the Sept. 11 attacks. Western politicians have expressed alarm at the gruesome details leaked by Turkish officials. Turkish President Erdogan said Tuesday Khashoggi’s death was likely a “planned operation.” David Ottaway, a Middle East fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, said Khashoggi’s death “represents a major crisis in the Trump administration’s Middle East policy which depends heavily on Saudi Arabia to fight Islamic extremism and contain Iran.” In his final article for The Washington Post, which he filed the day before he went missing, Khashoggi lamented the lack of a free press in the region and how the authorities had crushed hope that the Internet would liberate information from their censorship and control. “Arab governments have been given free rein to continue silencing the media at an increasing rate,” he wrote. When he went into exile, most of his family remained in Saudi Arabia, including his adult children who were reportedly banned from leaving the country. (SD-Agencies) |