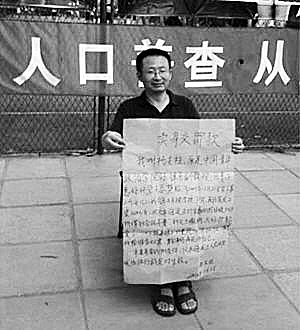

Martin Li YANG ZHIZHU, a 43-year-old associate professor in law, recently made headlines when he put himself up for sale to pay a 240,000-yuan fine imposed for having a second baby, a violation of China’s one-child policy. Officially titled the family planning policy, the 30-year-old policy was adopted in the late 1970s to control rapid population growth in an underdeveloped economy. Under the policy, most couples may only have one child, with some exceptions. Yang, who taught at Beijing Youth Politics Institute, was fired by the institute in March for his refusal to pay a “social maintenance fee” for his baby daughter, born in December last year. “Why should I pay money for having my own kid? It’s not human trafficking. It’s our right as citizens. There’s no need for birth control in China, as the birth rate is already quite low in big cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, and China is an aging country,” he told the China Daily in an interview in April, adding that the fine he refused to pay is 10 times higher than the price of a baby sold by human traffickers Yang is planning to take his case to court at the end of this month, hoping the attention could help bring a change to the controversial policy. Yang provides for his unemployed wife and two daughters by writing articles, mostly about the one-child policy, and is optimistic that the policy will be altered soon. “With everyone’s efforts, the change will come soon; without it, change will come slowly,” he told the Guangzhou-based Southern People Weekly last month. Yang’s case has fuelled an already heated discussion about the birth-control policy, which has been blamed for an aging population and an imbalanced gender ratio in China. Divided voice Vice director of the National Population and Family Planning Commission, Zhao Baige, said at a meeting in February that the one-child policy was an “important state policy that should be sustained in the next five years.” But debate on the subject in the academic world is ongoing — and increasingly lively. A once-unswerving supporter of the one-child policy, Hu Angang, a sociologist, has published articles calling for a raising of restrictions on second children. Hu says the one-child policy effectively controlled population growth at a time when Chinese had very low incomes and scarce per capita resources. However, he argues, China has changed dramatically and the country is now able to afford a change to its population policy with the rapid development of its technology and economy. He argues that China is seeing an increasing older population and decreasing junior population. A policy to curb rapid population growth has lagged behind social development. According to estimates by National Population and Family Planning Commission, China will have 355 million people over the age of 60 by 2030, becoming a “grey society.” China’s birth rate has declined dramatically. According to a national survey in 2005, China’s birth rate was only 1.33, much lower than 2.0, the “replacement level” in demographics. According to demographics, a country should increase its population when its birth rate drops below 2.0. “The general time limit for a public policy is less than 10 years in China. However, the one-child policy is the only one unchanged,” Hu says. One population expert, Yi Fuxian, says that, while a decrease in the workforce will weaken consumption, the need to feed and take care of a large number of seniors will weaken consumption still further. Yi cited Japan as an example in which the country’s economy is being held back by a large elderly population. However, Ma Li, the former director of the China Population and Development Research Center, says allowing a second child would do little to reduce the aging population. Instead, the problem could be solved through increasing employment, improving the quality of the workforce and tapping the potential of more senior working people. She argues conditions are “not ripe” to promote a second-child policy. Hou Dongmin, director of the population resource environment economics department of Renmin University of China, agrees. He says with its large population, China can ill-afford to lift its birth control policies. Besides the aging problem, other factors such as the economy, environment and resources should also be considered when calling for change, Hou says. Hou adds that shortages in the workforce should not be attributed to the aging trend: most employers only hire young people, leaving a large number of people aged between 40 and 50 unemployed. He says that Japan became an aging society in the 1970s, but its unemployed population has risen to almost 3 million. “The aging problem cannot be solved through an increasing birth rate,” Hou concludes. Pilot program Starting in 1985, a second-child policy was piloted in Yicheng, a county in Shanxi Province. Under the policy, married women in the county were recommended to have their first baby at the age of 24, and have the second at around 30. A third child was forbidden. There were 278,000 people in the county, which consists of 17 villages and towns. Surprisingly, in the years leading to 2000, the county’s population grew by only 20.7 percent, lower than the national growth rate. The initiator of the pilot program, Liang Zhongtang, a Ph.D. supervisor at Shanghai Academy of Social Science, said that, according to the Yicheng statistics, allowing a second child will not lead to a rapid population increase; on the contrary, population growth will slow. However, the experience in Yicheng has not had an effect on the population policy, according to Liang. Change to come? China launched its sixth national census earlier this month, as directed by Vice Premier Li Keqiang. “The whole country is counting the population born after 2000, which should be a preparation for a change to the population policy,” said Yi Fuxian. After the census, there would be in “big adjustment” to the population policy, Yi said. In an open letter issued by the Central Government, the one-child policy was expected to be changed after 30 years of its adoption as population growth has slowed. The deadline is approaching. |