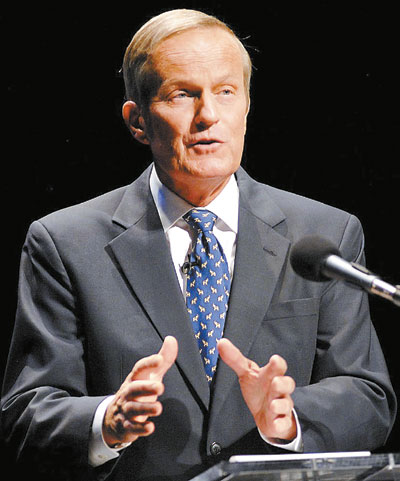

From Colorado to New Hampshire to Illinois in the United States, Democrats are already using the incendiary comments about rape made by the Missouri congressman and Republican Senate candidate as a political bludgeon. In interviews, news releases and tweets, they’ve blasted Todd Akin for saying victims of “legitimate rape” are able to naturally prevent pregnancy and tried to tie their opponents to legislation he’s supported. UNTIL this week, Missouri Republican Senate candidate Todd Akin was virtually unknown beyond his suburban district. He was associated more with his deep religious convictions than any legislative achievements. The Akin uproar began Aug. 19, when he was asked on St. Louis television about his abortion position. Addressing the issue of exceptions, Akin, a six-term member of the U.S. Congress who is backed by Tea Party conservatives, made it clear that his opposition to the practice was nearly absolute, even in instances of rape. “If it’s a legitimate rape, the female body has ways to try to shut that whole thing down,” Akin said. “But let’s assume that maybe that didn’t work or something: I think there should be some punishment, but the punishment ought to be of the rapist, and not attacking the child.” The comments, made during an interview with KTVI-TV that was posted Aug. 19 on the station’s Web site, provoked howls of outrage from Democrats and women’s rights organizations. Senator Claire McCaskill, the Democrat who will face Akin in the November election, immediately took to Twitter with a blunt response. “As a woman and former prosecutor who handled hundreds of rape cases,” she wrote, “I’m stunned by Rep. Akin’s comments about victims this A.M.” There were calls from within his own party, as well as from Democrats, for him to quit the current Senate race in Missouri, where he is running against incumbent McCaskill. U.S. President Obama called Akin’s remarks “offensive.” Presumptive presidential nominee Mitt Romney called them “insulting.” Akin did say that he misspoke, and that he meant to say “forcible rape,” not “legitimate rape.” In an apology, he said, “Rape is never legitimate … I used the wrong words in the wrong way.” That sparked a new round of fire, with observers questioning the difference between rape and “forcible rape.” Long before his comments about women’s bodies and “legitimate rape” made him a potential flashpoint in the fall campaign, Akin was a favorite among home-schooling organizations and conservative church groups in the area where his relatives have lived for generations. He seldom authored bills or sought wider recognition. Now Akin could help shape the national political debate in a Senate race that leaders of his own party don’t believe he can win, and they’re worried he’ll drag other Republicans down with him. But he insisted he will remain in the race to promote his anti-abortion beliefs, despite pressure from Romney and other top Republicans he called “the party bosses” to step aside for the good of his party. Akin has proclaimed that his success comes from not paying attention to politics. His campaign isn’t run by a political operative but by his eldest son, Perry. His unwavering opposition to abortion, support for prayer in school and gun rights, and disdain for big government have attracted a solid base of support in an increasingly conservative state. “One thing that has drawn me to Todd is his faith,” said Don Hinkle, director of public policy for the Missouri Baptist Convention. State Rep. Dwight Scharnhorst, a St. Louis County Republican, said “of all the people in Washington, D.C., if I had to rate one person that I would trust to hold my wallet or keep my grandchildren over the weekend, Todd Akin would be at the top of the list.” For the Akin camp, the big question, for the moment at least, is whether his campaign will be able to raise enough cash to fight a defensive TV ad war in the high-stakes Kansas City and St. Louis media markets. Bill Hillsman, a veteran campaign consultant in Minneapolis, sees some fundraising potential for Akin. His decision to stay “has less to do with social conservatives in Missouri and more to do with a calculation that national money will come back to him,” Hillsman says. “If the Republicans are stuck with him, they’re not going to abandon him, because it’s Missouri.” Depending on how polls and fundraising pan out in the next few weeks, Akin could still drop out of the race. According to Missouri law, he could withdraw as late as Sept. 25 by petitioning a state court. But that petition could be challenged by Missouri’s secretary of state, and a court case could dredge up the controversy just over a month before the election. With Akin regarded as damaged goods, Democrats now see improved chances for retaining control of the U.S. Senate in November, when the Republicans need to pick up four seats to secure a majority. But analysts say there is also the chance that Akin’s predicament could rally conservative and religious voters behind him on the U.S. election day. The 65-year-old Akin ascended in Missouri politics largely on his own. He grew up on a farm outside St. Louis, earned an engineering degree and went to work at the now-bankrupt Laclede Steel Co., which his great-grandfather started. He and his wife, Lulli, settled on land in St. Louis County owned by Akin’s father. Each Independence Day he dresses in colonial attire as his family hosts a party for the neighborhood. The Akins home-schooled their four sons (three of whom graduated from the Naval Academy and became Marine Corps officers) and two daughters. Lulli Akin’s involvement in home-schooling groups helped create the base of support that has long sustained her husband’s political career. Akin, a member of the conservative Presbyterian Church in America, earned a master’s of divinity degree from Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis in 1984. He never became a pastor but four years later won a seat in the Missouri House, where he established a track record as a staunch abortion opponent and supporter of gun rights. Faith is never far from his mind. In a fundraising e-mail sent to supporters Wednesday, Akin said he was accountable only to God and the voters, not “party bosses.” His anti-establishment streak started with his first run for the U.S. Congress. In 2000, party elders favored Gene McNary, a former St. Louis County executive who served in the George H.W. Bush administration and ran previously for governor and senator. Despite being an underdog, Akin defeated McNary by 56 votes on a day when torrential rain kept turnout at 17 percent. Akin’s disregard for the advice of party elites can be seen throughout his congressional tenure. While debating Bush’s Medicare prescription drug benefit in 2003, House leaders assiduously courted rank-and-file members to vote for the legislation. Akin refused, saying the program would blow up the federal budget and attract more illegal immigrants. He also voted against Bush’s No Child Left Behind education package. But he is well known in Washington for his spirited pursuit of legislation on social issues, even in cases where it stands no chance of becoming law. Akin has sponsored or cosponsored a raft of legislation affecting abortion, including a proposal that would ban all federal funding for abortions. His efforts have won him the support of conservative groups such as the Family Research Council, which was one of few organizations to stand by him after the rape remarks. Akin was always something of an outsider in the U.S. House Republican caucus. He has relatively few friends in the caucus and tends to eschew House social gatherings. Inside the Capitol, Akin is considered amiable, if removed. He is generally friendly and cordial with individual members, including Democrats (SD-Agencies) |