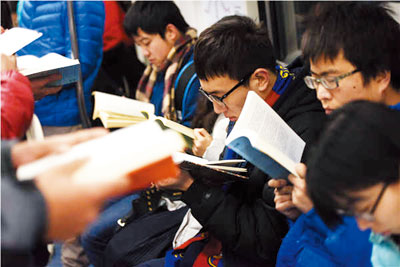

WANG CHONG and his friends gathered at underground train stations in Beijing, Shanghai and Wuhan for a few days in January hoping to get noticed. As they got in and out of coaches — and they did quite a bit of that — they made sure fellow commuters saw them glued to the books they were carrying. The flash mob was trying to raise awareness of the benefits of reading among Chinese, said Wang, who initiated the activity. “It’s time for us to pay more attention to our inner lives,” the 27-year-old Beijinger said of what he perceives as the need to read. He received a master’s degree in philosophy three years ago, and reading has become an important part of his life, he said. In the past year, many Chinese like Wang have spent money buying books — both offline and online. Since 2014, the goal of building a “nation of readers” has been included in the annual Report on the Work of the Government. The market value of printed books grew 10 percent in 2014 and 12.8 percent in 2015, according to OpenBook, an industry monitor. Dangdang, China’s largest online bookseller, sold 500 million books in 2015, rising from 330 million the previous year. JD.com, another leading online bookseller, sold 200 million copies last year — an average of 12 printed books for every online user. In 2014, Chinese read 4.56 copies of offline books on average, as compared with 4.77 in 2013. While the purchase of offline books went up, people spent at least 30 minutes on average reading books on smartphones and other devices last year. Last year’s best seller was the coloring book “Secret Garden,” according to OpenBook. Dangdang sold some 1.5 million copies. Other popular titles in 2015 included “The Kite Runner” by Khaled Hosseini, “Unworried Store” by Higashino Keigo and “Pingfan de Shijie” (“Ordinary World”) by Lu Yao, according to OpenBook. When the Chinese stock markets hit their highest point last year, books on investment and finance peaked in sales, according to Dangdang. In 2015, the most popular purchase among Chinese in their 40s and 50s was “The Lost Nutriology: Away From Diseases.” People born a decade or two later loved “Zero to One: Notes on Startups” or “How to Build the Future,” among similar books. For younger Chinese, the majority of the books they bought were on English and politics, the online bookstore said. The popularity of some Chinese TV series also led to the sale of novels on which they are based, including “Faerie Blossom,” “Nirvana in Fire” and “Legend of Miyue.” In general, leading online bookstores, including Dangdang and JD, said Chinese bought a lot of self-help books last year. According to a survey by Beijing Normal University, Chinese still prefer printed books. Among the nearly 30,000 people who took the survey online, nearly 51.9 percent say they like reading printed books, followed by 26.8 percent who like reading on smartphones, and others who read on computers. Dangdang, with 20 million digital readers, saw about 100 million copies of books downloaded in 2015. The average time readers spent on its reading app surpassed an hour per day. But it is still very hard to survey digital books in China because of piracy issues, said Yao Hong, marketing director of OpenBook. Yu Hong, managing director of Amazon Kindle, said at the Beijing International Book Fair in August that in the last three years, the download volume of books on Kindle has been growing. But Kindle users read only 42 percent of the books on the e-reader. The rest are read offline. As the government is advocating more reading and is building more libraries, the industry of printed books will see at least 10 years of golden development, Xu Jianhua, a professor at Nankai University, said in an interview with Chinaxwcb.com, a site under the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television. (China Daily) |