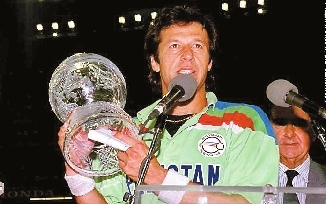

POLITICIANS the world over would kill for a name as recognizable as Imran Khan. Arguably one of the best all-around cricket players in the history of the sport, skilled at both batting and bowling, Khan dominated the pitch in the 1970s and ‘80s. His glowing career culminated in a World Cup win for Pakistan in 1992, in which he told his team to “fight like cornered tigers,” sporting T-shirts of the animal as a symbol of his tenacity. He swung between life in conservative Pakistan and the liberal West, and was a flamboyant celebrity whose romances often made headlines. His nine-year marriage to — and divorce from — British heiress Jemima Goldsmith was a fixture of the celebrity gossip columns. In a nation obsessed with cricket, Khan has cleverly engineered his legendary status to transition into a career in politics. And after some two decades of political life, Khan declared victory in the nation’s elections. The 65-year-old has swapped his former reputation as a playboy for one as a serious politician and devout Muslim, promising the Pakistani people he would reform the country and clamp down on corruption, a scourge that affects every aspect of public life in Pakistan. “Corruption is eating away at this country like cancer. There’s one law here and there’s one law out there. We will set an example, that the law is equal to everybody. The reason the West is so far ahead is because there is law and order in place there. Their institutions are strong, their justice system is strong,” he said in his victory speech, according to a translator. Khan founded his center-right Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), otherwise known as the Justice Party, in 1996 and has been eyeing leadership for years. He gained supporters over his criticism of the U.S. drone strikes on Pakistan, which target terror networks but often claim Pakistani civilian casualties. According to Mosharraf Zaidi, a newspaper columnist and political analyst, Khan adopted a hardline, religious persona to appeal to a wide base of voters. Khan has also benefited from the downfall of his political rival, former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, who was declared unfit for office in 2017 and was recently sentenced to 10 years in prison on graft charges. “We will run Pakistan like it has never been run before,” said Khan during his first televised address after his election win. He did so below a picture of a young Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the nation’s revered founder when it won independence from the British rule in 1947. Khan outlined a blueprint for a “New Pakistan” modeled on Jinnah’s vision. Malnourished kids would have enough food. Poor farmers would get more cash. The rich would pay taxes. Corruption would end. Terrorism would stop. Minorities would feel safe. And Pakistan would get along with everybody—even archrival India. Khan’s anti-corruption stance has proven to be “the most effective tool in his political arsenal,” Zaidi said. But some of Khan’s associates and political allies also stand accused of corruption, and there is skepticism he will be able to bring a clean government to power as effectively as he claims. While Khan has been a figure in Pakistani politics since the 1990s, his popularity has surged in recent years as Pakistan’s middle class has grown angry and disenchanted, according to Zaidi. Pakistan has failed to kick-start its economy and is on the brink of crisis, with a spiraling currency, persistent inflation and high levels of debt. Khan’s first challenge as the prime minister will be averting a financial crisis: Dwindling foreign reserves and a ballooning current account deficit have forced the central bank to devalue the currency four times since December. But Zaidi warns that Khan is a populist, and questions how much he might challenge Pakistan’s restrictions on civil liberties. Khan was also widely seen as the preferred candidate of the country’s powerful military, which has directly ruled Pakistan for almost half its independent existence since 1947, and has maintained an outsized influence over politics throughout that period. The country is divided into two camps, said journalist and former Pakistani ambassador to the U.S. Husain Haqqani: “Those who think the military has a right to run the country and those who don’t.” A lot of the former have rallied to Khan, he said. “The groups that benefited from military rule, they don’t like the political class that share this power,” Haqqani said. “Their disaffection is with democracy. [Khan is a] pro-establishment populist, not an anti-establishment populist.” Khan has had an enchanting life, though not always a consistent one. Born to a privileged family, educated at Oxford, a lover to many beautiful and famous women and a superstar athlete considered one of the best in cricket’s history, his experiences couldn’t be more different from those of most Pakistanis. He reached heroic status in 1992, captaining Pakistan’s cricket team to a World Cup final victory over England. It was an immense moment of national pride, and Khan was at the center of it. He was 39 and nursing a shoulder injury. He also built a reputation as a playboy who hung out at London’s posh nightclubs with the likes of Mick Jagger and Sting. A few years later, he went through a soul-searching conversion. He raised millions of dollars to build a cancer hospital for the poor (his mother had died of cancer) and he started to become more deeply interested in Islam. He moved away from the limelight and dating celebrities, saying that kind of life had never been very satisfying. “It looks from the outside very glamorous, great, but actually it’s not,” he told a British newspaper. “It’s these transitory relationships. They’re pretty empty.” In 1996, he founded his Justice Movement. His party struggled in obscurity for years, barely winning any seats in Pakistan’s legislature, and for a time, Khan the superstar became Khan the joke. A Pakistani newspaper ridiculed him as “Im the Dim,” while some others called him “Imran Khan’t.” The other two major parties, Sharif’s party and the Pakistan Peoples Party founded by the Bhutto family, proved better organized. They had established vast patronage networks throughout the country. In many areas, landlords and tribal chiefs still command enormous sway. Such grandees, if given the right incentives, can deliver huge blocks of votes, which Khan’s scrappy political outfit struggled against. But even during these years, Khan attracted a passionate following. “Who will save Pakistan?” his supporters would cheer at his rallies. “Imran Khan! Imran Khan!” His clipped English, tall, athletic frame, and personal charm helped him win over a cross section of Pakistanis this time, from slum dwellers to wealthy expatriates who flew back just to vote for Khan. For all the fawning that Khan has enjoyed, he has also taken his lumps and shown a fair bit of resilience — particularly when it comes to the consuming attention given to his private life. His first wife Goldsmith was a British socialite with a Jewish heritage who was friends with Princess Diana. Soon enough, Khan was accused by some Pakistanis of being controlled by a Zionist conspiracy, which he laughed off. His second wife recently published a memoir that included allegations of lurid indiscretions in Khan’s private life; he has let that roll off his back as well. His third and current wife is known as a spiritual healer; already many Pakistanis are quietly talking about the rituals Khan and his wife are believed to practice. Trying to sum up what Khan stands for, Ashutosh Varshney, the director of the Center for Contemporary South Asia at Brown University, said: “Imran is a maddening medley of an incredible sporting talent, an incorrigible international playboy and a vengefully ambitious politician.”(SD-Agencies) |