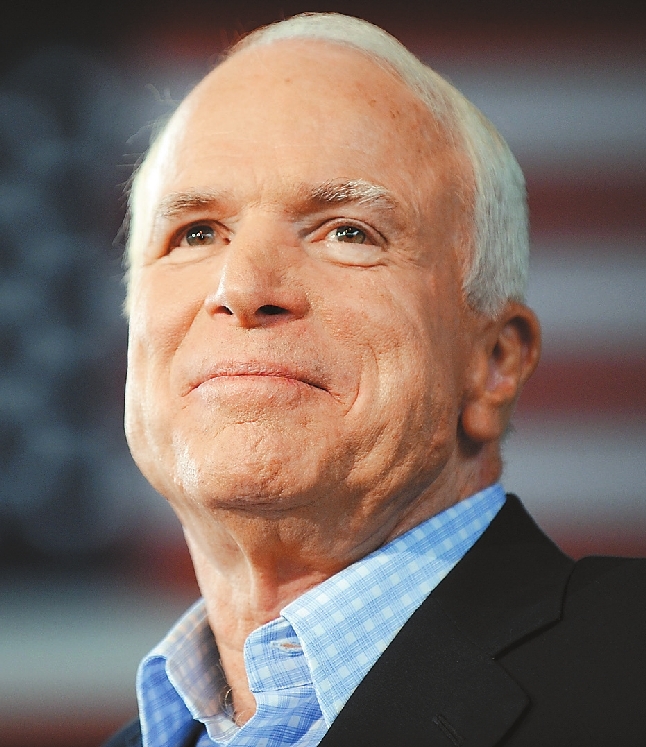

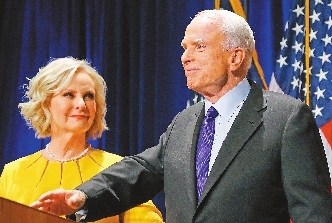

JOHN MCCAIN, the son and grandson of U.S. four-star admirals, was bred for combat. He endured more than five years of imprisonment and torture in Vietnam as a young naval officer and went on to challenge friend and foe through his singular temperament — sometimes angry, often funny, always ardent. He was an essential element of the nation’s political conversation for half a century. Now he is gone, leaving behind a storied life and a tear in America’s political fabric. During three decades of representing Arizona in the Senate, he ran twice unsuccessfully for president. He lost a bitter primary campaign to George W. Bush and the Republican establishment in 2000. He then came back to win the nomination in 2008, only to be defeated in the general election by Barack Obama. A man who seemed his truest self when outraged, McCain reveled in going up against orthodoxy. The word “maverick” practically became a part of his name. All living former U.S. presidents lined up to praise McCain’s deep integrity. “We are all in his debt,” said Obama. “We shared, for all our differences, a fidelity to something higher — the ideals for which generations of Americans and immigrants alike have fought, marched and sacrificed.” McCain “was a man of deep conviction and a patriot of the highest order,” said Bush. “It’s been quite a ride,” McCain wrote in a memoir published in May. “I’ve known great passions, seen amazing wonders, fought in a war and helped make peace. I made a small place for myself in the story of America and the history of my times.” “He was a great fire who burned bright, and we lived in his light and warmth,” said Meghan McCain, one of the late senator’s seven children. McCain was born Aug. 29, 1936, in the Panama Canal Zone and into a family whose military lineage included an ancestor who served as an aide to Gen. George Washington during the Revolutionary War. The middle of three children, McCain manifested his famously hot temper early: As a toddler, he would hold his breath until he blacked out. His tantrums were so severe that a Navy doctor advised his father and mother, the former Roberta Wright, to drop him, fully clothed, into a bathtub of icy water at the first sign of an outburst. After transient early years spent mostly at military bases, McCain enrolled at the U.S. Naval Academy, which he later recalled as “a place I belonged at but dreaded.” At Annapolis, he rebelled against the hazing and the regulations and racked up so many demerits that he was at risk of expulsion. (That, too, was something of a family tradition.) As McCain often boasted later in life, he graduated fifth from the bottom of the 899-member class of 1958. From there, he headed to Pensacola, Florida, to be trained as a Navy pilot. “As a boy and young man, I may have pretended not to be affected by the family history, but my studied indifference was a transparent mask to those who knew me well,” the senator wrote in a 1999 memoir of his early life, “Faith of My Fathers,” co-authored by Salter. “As it was for my forebears, my family’s history was my pride.” Sen. McCain also became involved in a serious romance, with Carol Shepp of Philadelphia, whom he had known since his days at the academy. They wed in July 1965, and he soon adopted her two sons from a previous marriage, Douglas and Andrew. The couple later had a daughter, Sidney. On Oct. 26, 1967, McCain was on his 23rd mission and his first attack on the enemy capital, Hanoi. His plane was shot and he was captured by Vietnamese soldiers. So began five years of imprisonment, nearly half of it spent in solitary confinement. During that time, his only means of communicating with other prisoners was by tapping out the alphabet through the walls. At first, his family was told that he was probably dead. The front page of the New York Times carried a headline: “Adm. McCain’s Son, Forrestal Survivor, Is Missing in Raid.” The Vietnamese, however, perceived that there was propaganda value in the prisoner. They called him the “crown prince” and assigned a cellmate to nurse him back to health. Shortly before his father assumed command of the war in the Pacific in 1968, McCain was offered early release, but he refused. “I knew that every prisoner the Vietnamese tried to break, those who had arrived before me and those who would come after me, would be taunted with the story of how an admiral’s son had gone home early, a lucky beneficiary of America’s class-conscious society,” McCain recalled. “I knew that my release would add to the suffering of men who were already straining to keep faith with their country.” In March 1973, nearly two months after the Paris Peace Accords were signed, McCain and the other prisoners were released in four increments, in the order in which they had been captured. He was 36 years old and emaciated. The effects of his injuries lingered for the rest of his life: McCain was unable to lift his arms enough to comb his own prematurely gray hair, could only shrug off his suit jacket and walked with a stiff-legged gait. McCain had hoped to remain in the Navy, but it became clear that his disabilities would limit his prospects for advancement. McCain’s marriage, meanwhile, frayed and fell apart. While he and his wife were separated, McCain visited Hawaii, where he met Cindy Hensley, the daughter of a wealthy Arizona beer distributor. A few months after his divorce became final in 1980, he married Hensley. The couple had three children. They also adopted a daughter, whom Cindy had met while visiting an orphanage in Bangladesh. Besides his wife and seven children, survivors include his 106-year-old mother. In 1986, he was elected in a landslide to the Senate, replacing the retiring Barry Goldwater, one of the most influential conservative politicians of the 20th century. McCain regularly struck at the canons of his party. He ran against the GOP grain by advocating campaign finance reform, liberalized immigration laws and a ban on the CIA’s use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” — widely condemned as torture — against terrorism suspects. To win his most recent re-election battle in 2016, for a sixth term, he positioned himself as a more conventional Republican, unsettling many in his political fan base. But in the era of President Donald Trump, he again became an outlier. The terms of engagement between the two had been defined shortly after Trump became a presidential candidate and McCain commented that the celebrity real estate magnate had “fired up the crazies.” At a rally in July 2015, Trump — who avoided the Vietnam draft with five deferments — spoke scornfully of McCain’s military bona fides: “He was a war hero because he was captured. I like people who weren’t captured.” Once Trump was in office, McCain was among his most vocal Republican critics, saying that the president had weakened the United States’ standing in the world. He also warned that the spreading investigation over Trump’s ties to Russia was “reaching the point where it’s of Watergate size and scale.” McCain’s most dramatic break with Trump came nine days after the Arizona senator announced July 19, 2017, that he had been diagnosed with brain cancer. He returned to the Senate chamber, an incision from surgery still fresh above his left eye, and turned thumbs down on a GOP plan to replace the Affordable Care Act. McCain’s no vote, along with those of two other Republicans, sent his party’s signature legislative goal hurtling toward oblivion. “He was always ready for the next experience, the next fight. Not just ready, but impatient for it,” said his longtime aide Mark Salter, who co-authored more than a half-dozen books with the senator, including three memoirs. “He took enjoyment from fighting, not winning or losing, as long as he believed he was fighting for a cause worth the trouble.”(SD-Agencies) |