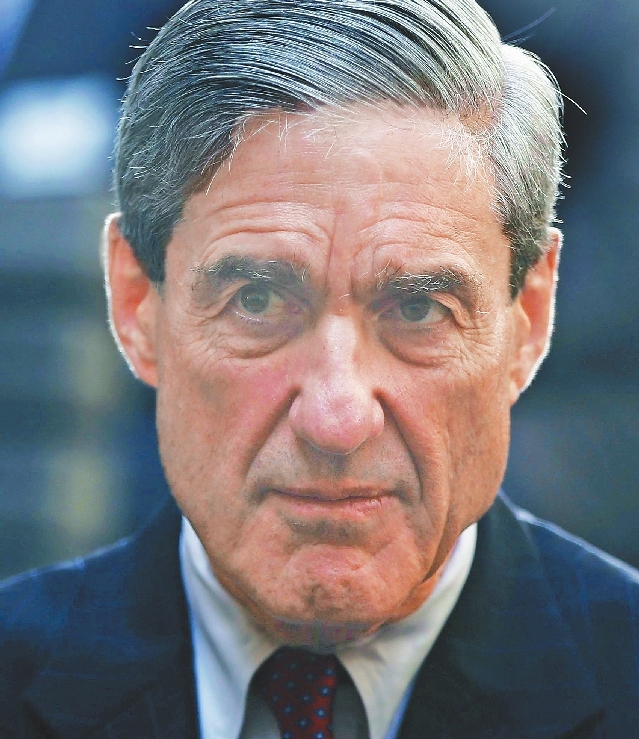

AS a prosecutor, Robert Mueller took on violent Hells Angels, mob bosses and foreign spies. At the end of his career, he was tasked with hunting the biggest target of all: the president of the United States. For two years, Mueller dug for the truth behind the most explosive political investigation in American history: Did Donald Trump or his campaign conspire with the Russian Government? And has the president been beholden to the Kremlin since his victory? The answer, revealed Sunday by Attorney General Bill Barr, was “no.” Mueller found no evidence of collusion, allowing Trump to declare “complete exoneration” even as questions of obstruction of justice remained. It came after two years of intense political pressure and scrutiny that the veteran criminal prosecutor was uniquely well-prepared to handle. He was named director of the FBI just days before the Sept. 11, 2001 Al-Qaida attacks, which plunged him into an entirely new mission to protect the country from future terror plots. The appointment in May 2017 to investigate a president who, according to the suspicions, may have been compromised by Russians, was another weighty, unfamiliar mission. The enigmatic, stately Mueller, 74, took it on in absolute stealth and silence. In a town where leaks are currency and a bully pulpit is power, Mueller stayed invisible, communicating through sporadic indictments that revealed that he had politically explosive evidence of possible wrongdoing reaching into the Trump administration’s inner circles. Over two years, his crack team of seasoned counterintelligence agents, financial forensics specialists and organized crime prosecutors worked with uncommon speed for such a sprawling investigation to open and close cases. They indicted 34 individuals, including six former Trump aides, five of whom have pleaded guilty or been convicted at trial. Most of the rest — more than two dozen Russians charged with conspiracy to meddle in the 2016 election — are unlikely ever to face trial. But the indictment allowed Mueller to detail just how deep the threat to the country from Moscow’s election meddling was. Mueller’s team has been aggressive and focused, reflecting his reputation as a gruff taskmaster who demands speed and precision. This discipline has been especially important in countering Trump’s repeated accusation — more than 180 times on Twitter alone — that the operation was a politicized “witch hunt.” Mueller, the president said on Twitter in December, “is a much different man than people think.” “His out of control band of Angry Democrats, don’t want the truth, they only want lies,” Trump huffed. Despite the White House attacks, few in Washington thought there was anyone better than Mueller for the special counsel job. The one-time U.S. Marine served both Republican and Democratic presidents and was a patrician of the Washington bureaucratic establishment, deeply trusted to do the right thing no matter who that would upset or disappoint. “I think Bob Mueller is an American hero,” said Ty Cobb, who served as a top White House lawyer tasked with protecting the president during the first year of the Trump administration. But the man who had the fate of the presidency in his hands stayed silent and invisible, keeping politicians of both parties on edge, lawyers studying the constitution and journalists swarming. In two years, he was seen in public only a handful of times — at a restaurant, in a Washington Apple Store getting tech help with his wife and once crossing paths with Trump’s son Don Jr. in Washington’s National Airport. He spoke only via the details of court filings in each case, thousands of pages that offered a steady flow of puzzle pieces of what had the potential to become a big, coherent picture — or not. Beyond that: Nothing. No interviews. No press conferences. No tweets. No leaks. Mueller’s silence clearly made the White House and Republicans in Congress nervous. Mueller enjoys a certain mystique, depicted in fan memes as a “Star Wars” Jedi or a character from “Game of Thrones.” What his friends and former colleagues portray is a complicated person: relentless but circumspect, impatient but thorough, difficult but respected. Mueller, they say, is the kind of man who flicks the lights off and on at his home to inform guests that it’s time to leave a social gathering. As FBI director, he twice threatened to resign over matters of legal principle, winning the standoff both times, and was infamous for eviscerating ill-prepared underlings. “If indicting his own mother was the right thing to do,” said former FBI Assistant Director Tom Fuentes, “he would do it.” “He likes to follow procedures,” said David Kris, former assistant attorney general in the national security division of the Department of Justice. “And those procedures he sees as a safe harbor against the stormy seas of politicization.” Born in 1944 into a country at war, Mueller was given the name of his father, Robert Swan Mueller Jr., a Princeton grad who captained a Navy sub chaser in the Mediterranean and later became an executive at DuPont. The younger Mueller grew up in New Jersey and attended high school at St. Paul’s, an elite New Hampshire boarding school, where he played on the varsity lacrosse team with future Secretary of State John Kerry. Then he followed his father to Princeton, writing his senior thesis on African territorial disputes before the International Court of Justice. In college, Mueller met David Hackett, an older lacrosse teammate who became a role model. Mueller decided that, like Hackett, he wanted to join the Marines. After graduating in 1966, Mueller married his high school sweetheart Ann Standish and enlisted in the Corps. The following year, Hackett was killed by a sniper during his second tour in Vietnam. Mueller has said that Hackett’s death only strengthened his resolve to follow his classmate’s service. The commitment provides a window into the 22-year-old Mueller’s character: a young man with wealth, a new wife and no shortage of professional options chose to join the Marines during an escalating war. Mueller served in Vietnam for one year, but the stint would set the course for the rest of his life. “You can’t understand him without understanding his roots as a Marine,” said Lisa Monaco, his former chief of staff at the FBI and later homeland security adviser to former President Barack Obama. “His leadership style and his work ethic and his focus on leading by example and with integrity are all completely bound up and informed by his service as a Marine.” That Mueller survived his tour while others did not only heightened his sense of duty. “Perhaps because of that,” Mueller said during a 2013 commencement address at the College of William & Mary, “I have always felt compelled to try to give back in some way.” After law school at the University of Virginia, Mueller spent three years as a litigator in a private firm in San Francisco, then 12 years in the U.S. Attorney’s offices in San Francisco and Boston. In 1989, he went to work at the Justice Department, becoming head of its criminal division under Attorney General Barr — who later became his boss again, after being nominated for the same role by Trump. When George W. Bush became president in 2001, he picked Mueller to become FBI director. Seven days after his swearing-in came the Sept. 11 terror attacks. For the next 12 years, under Bush and later Obama, Mueller reshaped the bureau to focus on intelligence and counterterrorism along with traditional criminal law enforcement. For all his admirers, plenty of employees at the bureau disliked Mueller. Mueller acknowledges his impatience. In his address at William & Mary, he recalled that during his days at Justice he’d often cut off attorneys by saying, “What is the issue?” One evening, he said, his wife started telling him about a hard day. He interjected with the same curt question. She did not appreciate it. “I am your wife,” he recalled her saying. “I am not one of your attorneys. Do not ever ask me, ‘What is the issue?’ You will sit there and you will listen until I am finished. “That night, I did learn the importance of listening to those around you — truly listening — before making judgment, before taking action,” he continued. “I also learned to use that question sparingly, and never, ever with my wife.”(SD-Agencies) |