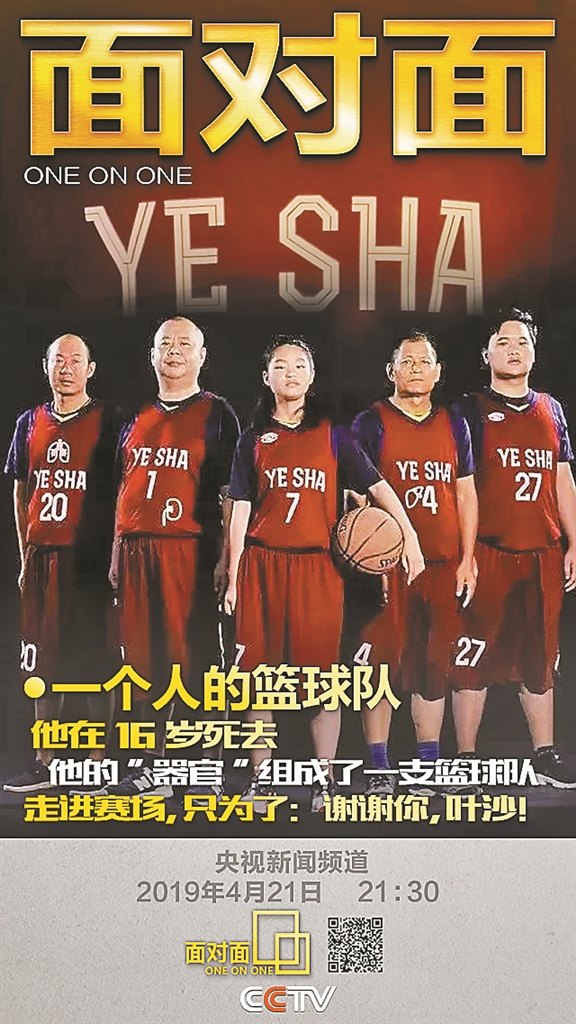

A THUMP. Another thump. And another one. The sounds reverberated through an empty stadium in Inner Mongolia. Sunlight poured in through the windows, illuminating the court and the surrounding green walls. Liu Fu clumsily bounced a basketball, held it up, tried to shoot for the hoop and missed. Liu didn’t know how to play basketball. His thick, rough hands were more used to holding a drill than a ball. However, the former migrant worker would stand in front of hundreds of thousands of people and display his awkward basketball skills in the Chinese women’s league All-Star Game on Jan. 27, 2019, in memory of a basketball-loving boy whom he had never met but who now was already a part of his life, literally. Liu’s memory often flashed back to the night of April 27, 2017, when he lay in the surgery room of the Second Xiangya Hospital in Hunan Province waiting for an organ transplant. Out of the corner of his eye, he saw someone come into the room, carrying a box. “They are of excellent quality,” were the last words Liu heard before he lost consciousness, according to a story released by the Beijing News. In the box were the lungs of a 16-year-old boy, Ye Sha, who had died early that morning. In retrospect, April 27 was an ordinary day for most people in the world, yet on this very day a lot of people saw their fates forever changed — among them, a lively boy whose clock of life stopped at 16, two devastated parents and seven patients, some of whom were terminally ill. Ye Sha Just a day before, Ye was a happy high school freshman whose favorite pastime was playing basketball. The 180cm-tall Ye seemed to have everything. Besides being athletic, he was also an academic star at his high school in Changsha, winning the top award at his school’s mathematics competition, and was considered a model student. No one could have imagined that death would soon seize the industrious and high-spirited student. Ye called his father from school on April 26, 2017, saying that he had a terrible headache. Ye’s father told him to go home and hurried home himself. When he opened the door, he found his son lying unconscious on the floor. He rushed Ye to the Brain Hospital of Hunan Province, a 10-minute drive from his home, but it was too late. Doctors exhausted all possible means of emergency treatment on Ye and the diagnosis was dire — severe intracranial hemorrhage, weak breath, a deep coma and no reaction to outside stimulation. The worst moment came at 7:20 the following morning. Ye was pronounced brain-dead less than three weeks before his 16th birthday. At around the same time, organ donation coordinator Meng Fengyu received a call from the Brain Hospital telling her there may be a potential organ donor. Meng, then 26, raced to the ICU ward and saw doctors speaking to Ye’s parents. Doctors explained Ye’s irreversible situation and mentioned the possibility of organ donation. Naturally, the recommendation was met with a resolute and desperate “No” from Ye’s mother. Hearing this, Meng backed away. She did not even walk into the room because she understood how heartbroken the parents were at that time — Ye was their only child, and he was such a brilliant boy. Meng understood their previous refusal. In a country with several thousand years of history, the idea of cremating a family member’s body which is not “complete” is still not acceptable for many Chinese, especially in older generations. As the ancient philosopher Confucius put it over 2,500 years ago, people’s bodies — including every hair and piece of skin — come from their parents, and they must not be injured or wounded. This was considered the beginning of filial piety, a central value in traditional Chinese culture. Consequently, when China started a voluntary organ donation trial in 2010, only just over 1,000 people registered. However, Meng was very surprised to find that less than half an hour after she had left the hospital, another call came in, this time from the Hunan Red Cross telling her the parents of a 16-year-old brain-dead boy wanted to learn more about organ donation. “I was astonished,” Meng said. “Wasn’t this call about Ye’s parents? What happened in the past half an hour that made them totally change their minds?” Ye’s father said that in that half hour, he absorbed the fact that his son would never return, and he was determined to realize his dream for him. “His dream was to become a doctor, to save lives,” he said. Ye’s parents eventually met with Meng and signed the organ donation paper. “He ticked in the checkboxes in order — the corneas, the heart, the liver, the kidneys. He was fast and determined,” Meng recalled. Once he had almost finished filling out the form, the father paused at the choice of “lungs.” “Shouldn’t we leave at least one organ to our child?” he asked himself. However, his hesitation was soon erased when doctors told him a terminal pneumoconiosis patient would rely on his decision for the chance of life. “I wanted to leave an organ to my son. But his lungs can save a life, so I decided to donate them as well,” Ye’s father said. “Looking back, I believe I did the right thing,” he continued, clearing his throat again. “At least he left something behind in the world. Our hearts are not completely empty. The biggest regret is that we did not donate more. I later learned that his organs could have saved up to 11 people,” the father said. Liu Fu Now Ye’s perfect lungs were in Liu’s body. When Liu regained consciousness the next day, he immediately knew that the surgery was successful. In almost 20 years, he had never breathed so comfortably. For 20 years, the then-47-year-old Liu could not work, and in the last couple of years before his surgery, he could barely breathe; his rotten lungs tortured him so much that he felt like the living dead. Liu, a mingrant mine worker from Lianyuan County in Hunan Province, has struggled to support his family. The job cost him too much, damaging his lungs and dragging him to death’s door. Liu was diagnosed with pneumoconiosis in 1998, and in the following years, he was like a prisoner on death row, waiting for the day to come. Liu did want to give up hope without a fight. He and his son once went to a local hospital in nearby Loudi City where a doctor told him his case was “hopeless unless he receives an organ transplant.” Such an operation would cost over US$70,000, making it an option Liu would never be able to afford. On his way back home, Liu and his son bought a coffin. Luckily, a phone call from the Hunan Red Cross came. “I never expected I would have an organ transplant, even in my wildest dreams,” he recalled. The call was a follow-up interview with the family of the organ donor. Liu’s wife had died after an accident in 2015, and he agreed to donate her liver and kidneys. Several months later, he was admitted into the Second Xiangya Hospital free of charge, waiting for the donated lungs. On Liu’s 42nd day in the hospital, the doctor told him to prepare for the operation. “I was told my lungs were from a 16-year-old boy about one week after I got out of the ICU. I was shocked. I can totally feel their pain as I am a father and also have a son,” Liu said. The double-blind rule of organ donation prevented Liu from getting in touch with Ye’s parents, but he managed to learn some things about his donor, including his hobby of playing basketball. That was why Liu jumped at the idea of organizing a basketball team with the recipients of Ye’s organs to honor the Ye family’s noble act when the China Organ Donation Administration Center reached him. Not all the organ recipients were willing to expose their privacy. Out of seven people, five joined in the campaign: Liu; 14-year-old Yan Jing and Huang Shan, each of them taking a cornea; Zhou Bin, recipient of Ye’s liver’ and Hu Wei, taking a kidney. They formed a team, appropriately named Yesha. WCBA All-Star Game The Yesha team’s performance may be the most special two minutes in the seven-year history of the Chinese women’s basketball league All-Star Game. As the main game went into a break, the five of them, in scarlet jerseys printed with their numbers and organ icons, filed onto the court, while on the big screen, a video telling the story of Ye and the team was displayed. “I am Ye Sha, Ye Sha’s lungs,” Liu said in the video. “I am Ye Sha, Ye Sha’s eye,” Yan Jing said. “I am Ye Sha, Ye Sha’s eye,” Huang Shan said. “I am Ye Sha, Ye Sha’s kidney,” Hu Wei said. “I am Ye Sha, Ye Sha’s liver,” Zhou Bin said. Their names were called out one by one by ceremony host Liu Xingyu, as the full-capacity 6,000 crowd welcomed them with a standing ovation, among them former NBA star and current Chinese Basketball Association president Yao Ming. Yao led the pack in the VIP seats to stand up, clapping his hands, while down on the court, the team’s opposing All-Star players wiped tears from their faces. The All-Star Game drew to close on Jan. 27, but it helped focus huge media coverage on Team Yesha and China’s organ donation drive, and triggered an explosion of volunteer registrations. In an interview two days after the game, China Organ Donation Administration Center official Zhang Shanshan told reporters that a total of 900,000 people had registered to donate their organs by the end of January. More than three months later, that number has exceeded 1.22 million. Ye’s parents did not attend the game, instead watching it later online. Papa Ye cried and Mama Ye’s insomnia was alleviated. “I received great comfort. When I saw them running on the court, it seemed like my son was still with us. Looking at the lives Ye Sha saved, I am truly happy for them. I believe I did the right thing, from the bottom of my heart,” he said. Losing their son left a permanent hole in their lives, as Ye’s parents now try to fill their time with the busy schedules of promoting organ donation and operating a home bakery. (Ye Sha, Liu Fu, Yan Jing, Huang Shan, Zhou Bin and Hu Wei are all pseudonyms.) (Xinhua) |