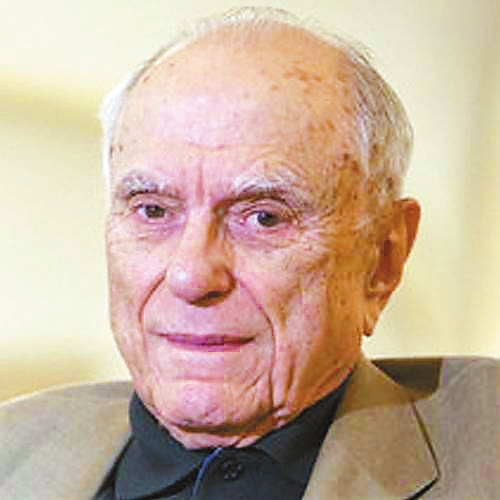

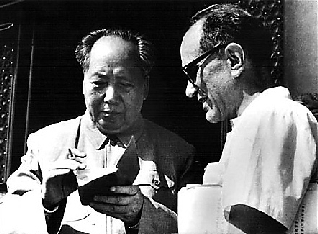

AFTER army service in World War II brought him to China, a young American and labor activist named Sidney Rittenberg stayed behind to help build a new China. Rittenberg, who was 98 when he died Saturday at a nursing center in Fountain Hills, Arizona, the United States, was widely considered one of the most powerful Westerners advising the Chinese Government in the 1950s and ’60s. Widely known as Li Dunbai in China, the South Carolina native who spent 36 years in China was called “a foreign member of the Communist Party of China (CPC) of excellence” by Chairman Mao Zedong. One of the very few foreign members of the CPC, he joined the United States Communist Party in college when he was 19. “I am American but I am China’s American,” he said in an 2011 interview with China Daily. In his autobiography, “The Man who Stayed Behind,” published in 1993, he wrote that he had no regrets over the years he spent in China. A week before his 98th birthday, celebrated Aug. 14, Rittenberg talked about present U.S. relations with China. “Watching the [U.S.] president on TV is like a comic hour. The only thing is, it ain’t funny. … Intelligent people are threatening the largest country in the world with destruction,” Rittenberg told U.S. media. He suggested, “Why not give up on the idea of destruction?” Rittenberg arrived in Kunming in 1945 right after the Japanese had surrendered unconditionally. At the age of 24, he was appointed to the U.S. Army’s Compensation Department for his proficiency in Chinese. Soon after his arrival, he met with a rickshaw puller who lost his only child in a car accident caused by a drunk American surgeon. The father received only US$14 in compensation and even gave some of the money to Kuomintang officials for writing the claim for him. “It struck me that he didn’t think he had any rights whatsoever — that impressed me very deeply,” Rittenberg told China Daily. He wanted to stay to help people like the rickshaw puller. As his interest in the Party grew, he became acquainted with the secret CPC members in Kunming via a newsboy and decided to stay in China when the U.S. army was ready to return. He relocated to the U.S. Army Headquarters in Shanghai and became acquainted with Soong Ching-ling, wife of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the forerunner of China’s democratic revolution. Soon he became an official of the U.N. Relief and Rehabilitation Administration in China, enabling him to remain in the country. “My heart was with the people. These were good people being wronged, being threatened,” he said. A chance encounter in 1946 with Mao sealed his ambition to stay on. “I walked in the door and there he was,” Rittenberg later recalled. “It was like a picture right out of history, and underneath that was the feeling, ‘I’m now part of history.’” Easygoing and charismatic, even in his second language, Rittenberg developed a rapport with Mao and Zhou Enlai. They discussed life in America, played cards, and watched the English-language films of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, two of Mao’s favorite comedians, as Rittenberg provided the translation. In 1946, Rittenberg helped establish the English Broadcast at Xinhua radio station and trained the first English broadcasters in China. What excited the 25-year-old young man was his arrival at Yan’an where he found an ideal new world. Everyone was equal and the system was democratic. He worked as the foreign expert at the Xinhua News Agency head office, taking charge of translation and editing, and advocating the Chinese communist cause to the outside world. The same year Rittenberg officially joined the CPC. “A real Party member needs to withstand trials and tribulations,” he said, recalling the experience of being wrongly jailed as a suspect “American spy” for six years from 1948. When he was released in 1954, he waived the chance to return to the United States, although he found out his second wife Wei Lin had applied for a divorce in 1952, as she had not heard from him since his departure. He wanted to stay in China and become a Chinese citizen, but after a talk with Zhou, he dropped the idea. “Zhou said ‘I want you to think, is it better to have one more Chinese Communist or to have one more American communist?’ So I understood. I never applied,” Rittenberg said. In the early 1960s, Rittenberg became a member of the translation committee for Mao’s selected works. His monthly salary was 600 yuan (US$92) per month, seven times that of his colleagues. Even Chairman Mao received only 404 yuan a month. He was well paid and lived with his third wife, Wang Yulin, and their three daughters and son in a Beijing suite luxurious even by Western standards, filled with priceless Ming dynasty antiques. But when he discovered an article about Jiao Yulu, a county-level CPC secretary who had dedicated his life to poverty relief, Rittenberg decided to change. “Compared to a communist like Jiao Yulu who had devoted himself wholeheartedly to serving the people, I enjoyed privileges and was alienated from the masses,” he said. So he took a pay cut, moved to a public office with the other translators and writers, and subjected himself to regular physical labor. In 1966, the “cultural revolution” began. For the second time he was wrongly jailed as a suspect “American spy” in 1968. His wife also suffered. He was released in 1977 and finally absolved of all charges in 1982. Rittenberg had new obligations to fulfill when China and the United States established diplomatic relation in 1979. That same year, he and his wife went to the United States to visit his mother and sister for the first time in more than 30 years. It was then that he made another important decision — to return to the United States. “U.S. understanding of China was very poor. So we decided to stay in the United States to promote Sino-U.S. friendship,” he said. He established Rittenberg & Associates, a consulting firm for American companies doing business in China. Although a two-person endeavor, with just him and his wife, it successfully helped big companies, such as Intel, Prudential Insurance, and Polaroid to develop their businesses in China. He made a half-dozen business trips to China annually and kept an apartment in Beijing. David Shrigley, a former Intel executive, told The Times in 2004 that Rittenberg helped Intel open a semiconductor plant in China in the 1990s. “He understands what’s really going on in a very nuanced way that proved tremendously valuable to us.” Rittenberg and Mike Wallace, the correspondent for CBS’ “60 Minutes,” forged a deep friendship that led to Rittenberg facilitating Wallace’s interview of Deng Xiaoping in 1986. “I always wanted to become a bridge between the United States and China,” he said. Rittenberg was born in Charleston on Aug. 14, 1921, to a Jewish family steeped in politics. His grandfather had been a prominent South Carolina legislator and served five terms in the state House of Representatives. Rittenberg’s father was president of Charleston’s City Council. His mother was the daughter of a Russian immigrant. After graduating from the Porter Military Academy in Charleston in 1937, he turned down a scholarship to Princeton to attend the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he majored in philosophy and graduated in 1941. After college, he became a labor organizer. He attributed his activist leanings to having witnessed the police brutalize a black man who had been seeking protection from a drunken and abusive white man. “I asked my aunt about it,” he told People magazine. “I told her, ‘It’s so unjust!’ She said. ‘There isn’t any justice. You get what you pay for.’” His first wife, Violet, a farmer’s daughter, divorced him soon after he was conscripted into the army in 1942 and sent overseas. Recognizing his talent for languages — he had learned French and Latin in prep school and excelled in German at Chapel Hill — the army sent him to its language school at Stanford University. He is survived by his wife, four children, and four grandchildren.(SD-Agencies) |