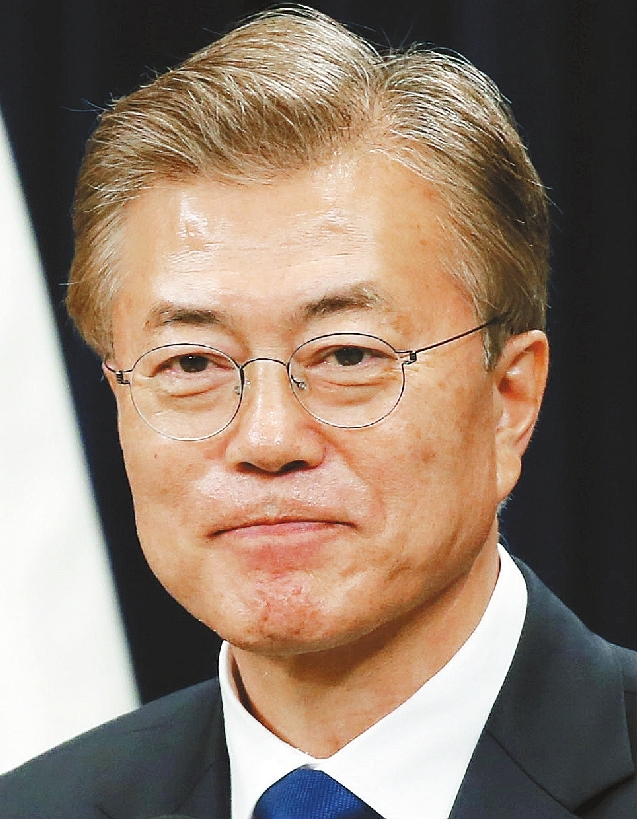

THREE years ago, South Korea’s Moon Jae-in was among the masses in the streets of Seoul seeking to oust a president accused of ignoring the people’s will. Now, his own presidency is facing a similar crisis. Moon was forced to issue a public apology Monday after his justice minister, Cho Kuk, bowed to a series of mass protests and resigned. The departure represented a stunning setback to Moon, who had only five weeks ago ignored corruption probes swirling around Cho and his family to put him in charge of the country’s justice system. The demonstrations and investigations have only intensified in the intervening weeks, with Cho’s home raided by prosecutors and lawmakers shaving their heads to protest the appointment. The conservative opposition — struggling since Moon helped impeach former President Park Geun-hye in 2016 — has climbed up to become level with the ruling Democratic Party in opinion polls. “The circumstances that brought down former President Park and started Moon’s administration are now bringing him down,” said Hong Sung-gul, a professor with Kookmin University’s Department of Public Administration. Moon and Cho “thought that pushing the criticism to the side would somehow make this go away, but it didn’t and it developed an even stronger opposition,” Hong said. The shift has increased the political peril for Moon just as he begins to prepare for nationwide parliamentary elections in April. The episode shows that Moon, a former civil rights lawyer, hasn’t broken the boom-and-bust cycle of South Korean presidents, who often see scandals mount and agendas stall in the second half of their single five-year term. Moon told a meeting of top secretaries Monday that he felt “quite regretful” for having “caused so much friction between the people.” He then took a swipe at the press, urging the country’s free-wheeling media to become more “trustworthy,” without elaborating. Moon already faced headwinds on two of his biggest agenda items: Reinvigorating the economy and securing peace with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). South Korea’s central bank has warned that the economy may not meet its 2.2 percent growth target this year and DPRK leader Kim Jong Un has resumed ballistic missile tests and mocked Moon’s efforts to mediate nuclear talks with U.S. President Donald Trump. Meanwhile, Moon’s government and Japan have escalated a nationalistically charged feud, putting pressure on both their economies and drawing rebukes from the United States. Moon’s approval rating hovered near an all-time low at 41 percent last week, according to Gallup Korea, compared with 84 percent immediately after his election in May 2017. Back then, Moon was riding high on a successful people-power campaign to oust, prosecute and imprison Park, the conservative bloc’s standard-bearer and the daughter of a former leader. Having lost to Park in South Korea’s 2012 presidential election, Moon, a former special forces soldier and pro-democracy activist, positioned himself as the only candidate qualified to reunite the country after the bitter divisions that opened up over Park’s allegedly corrupt relationship with her longtime friend and confidante Choi Soon-sil. At his inauguration, Moon pledged to “become the president for everyone.” Moon’s decision to appoint one of his former secretaries to the justice minister’s post despite the investigations drew comparisons to Park’s cronyism. Cho has denied wrongdoing in a range of issues involving him and his wife, including their children’s university applications and an investment in a private equity fund. The scandal caused the opposition bloc’s regular marches through Seoul to swell into the tens of thousands, while Liberty Korea Party (LKP) chief Hwang Kyo-ahn shaved his head in protest outside Moon’s office. The demonstrations spread to universities, where students accused the president of tolerating the sort of favoritism he had vowed to stop. The controversy overshadowed Moon’s stated reason for appointing Cho: Making prosecutions fairer by expanding ministerial oversight of investigations. Cho urged Moon to continue the effort in a statement Monday, saying he decided to “no longer put pressure on the president and the government with my family issues.” The opposition LKP — the successor of Park’s Saenuri Pary — has gained ground amid the scandal. A Realmeter poll released earlier Monday showed the LKP with about 34 percent of support, less than 1 percentage point behind the ruling party. “Moon’s biggest loss in this situation were the people in the middle — he read the people wrong,” said Choi Chang-ryul, a politics professor at Yongin University. “It may be hard for Moon to see his approval ratings bounce back up before the general elections next year.” Moon was born on the southern island of Geoje in January 1953 after his North Korean parents resettled in South Korea’s southeast. His father was a menial worker at a prisoner-of-war camp while his mother peddled eggs in the nearby port city of Busan, with the baby Moon strapped to her back, the politician wrote in his autobiography. As a boy, he often went to a Catholic church with a bucket to get free U.S. corn flour and milk powder. After entering Seoul’s’ Kyung Hee University in 1972, Moon joined a pro-democracy movement protest against the authoritarian rule of Park Chung-hee, the father of the ousted Park who ruled South Korea for 18 years until his 1979 assassination. In 1975, Moon was jailed for months for staging anti-government protests. Moon returned to school in 1980 only to be arrested again before being conscripted into the military’s special forces. After his discharge, he passed the bar exam and was admitted to the Judicial Research and Training Institute. He graduated second in his class but was not admitted to become a judge or government prosecutor due to his history of activism as a student. Moon chose to become a lawyer instead. His close friendship with Roh Moo-hyun, the former South Korean president who committed suicide in 2009 after being questioned over graft allegations, began in 1982 when they opened a law firm in Busan focusing on human and civil rights issues. Moon said their friendship changed his life. Both became leading figures in the pro-democracy protests that swept the country in 1987 and led to South Korea’s first direct presidential elections the same year. “I was always happy due to the fact that I was able to help others with what I had been trained to do,” Moon said in his autobiography. A year after Roh’s unexpected election victory in 2002, Moon joined the administration as a presidential aide, tasked with weeding out official corruption and screening candidates for top government posts, before rising to become his chief of staff. Assuming the presidency of South Korea in May of 2017, Moon set two objectives. He needed to revive the dormant economy that had been once one of the Asian Tigers and to restore a warmer relationship between the North and the South. More than two years in, Moon’s economic policies have achieved little and his diplomatic efforts to restore warmer relations with the North are only a facade. He can claim success in raising the per capita annual income to US$30,000, but that has been accomplished by increasing the minimum wage by 30 percent. The sharp rise in the minimum wage has struck already struggling smaller businesses which have little capital to invest in job creation. It has left the economy creeping, a sharply declining currency and a persisting 3.8 percent unemployment rate with youth unemployment at double the overall rate. To bring momentum to his efforts to improve inter-Korean relations and expand economic ties with Pyongyang, Moon has met up with Kim three times and become the first South Korean leader who has visited the DPRK capital in 11 years. But as Trump and Kim engage in an international probing game, Moon is increasingly being rendered irrelevant and is running out of time to act. (SD-Agencies) |