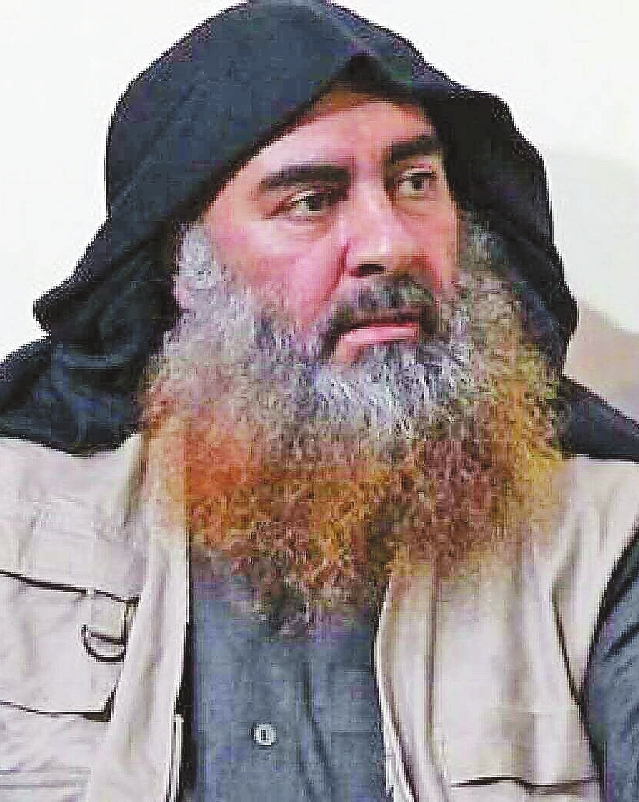

ABU BAKR AL-BAGHDADI, the ruthless leader of the Islamic State of Syria and Iraq (ISIS) who once controlled a vast swath of territory and tens of thousands of jihadist fighters, is believed dead in a raid by U.S. troops in northern Syria, bringing a dramatic end to a years-long U.S.-led hunt. Addressing the nation Sunday morning, U.S. President Donald Trump said a team of U.S. special forces targeted al-Baghdadi in a “dangerous and daring” overnight raid. During the operation, the ISIS leader was “crying and screaming” and attempted to flee through a tunnel, the president said. As U.S. forces and dogs approached him, al-Baghdadi detonated a suicide vest, killing himself and a group of children who he brought with him, according to Trump. “He died like a dog. He died like a coward,” Trump said, adding that he watched much of the raid in real time from the White House Situation Room. Trump said test results confirmed the identity of ISIS leader’s body, which he noted had been mutilated by the blast. There was no immediate confirmation by the Islamic State’s media arm, which is typically quick to claim attacks but generally takes longer to confirm the deaths of its leaders. The Syrian Observatory of Human Rights (SOHR) said the raid took place at a compound at about 12:30 a.m. local time to the west of the town of Barisha, a mountainous area about 40 km west of Aleppo overlooking the Turkish border. The area is a hotbed of activity by al-Qaida cells in Syria. SOHR said eight U.S. gunships and a fighter jet fired on targets in the area for about two hours, with messages blasted over loudspeakers in Arabic urging those in the compound to surrender. The group said nine people were killed. The Pentagon on Wednesday released the first government photos and video clips of the nighttime operation, including one showing Delta Force commandos approaching the walls of the compound in which al-Baghdadi and others were found. Another video showed American airstrikes on other militants who fired at helicopters carrying soldiers to the compound. Gen. Kenneth ‘‘Frank’’ McKenzie, head of U.S. Central Command, said the attacking American force launched from an undisclosed location inside Syria for the one-hour helicopter ride to the compound. Two children died with al-Baghdadi when he detonated a bomb vest, McKenzie said. He said the children appeared to be under the age of 12. Eleven other children were escorted from the site unharmed. Four women and two men who were wearing suicide vests and refused to surrender inside the compound were killed, McKenzie said. Al-Baghdadi’s reclusiveness fed rumors of his demise, with many news outlets carrying speculative reports of his death, all of which proved to be untrue. Each time, he resurfaced in audio recordings, and later videos, thumbing his nose at the world. American officials who worked in the Obama administration say that for all of 2014, 2015 and 2016 there was not a single time when they believed they had solid intelligence about al-Baghdadi’s whereabouts, even as numerous other senior Islamic State leaders were hunted down and killed, including al-Baghdadi’s No. 2. Most of the world learned of al-Baghdadi in July 2014, when he mounted the pulpit of a mosque in Iraq to declare himself the head of a growing terrorist organization. He then appeared in a video in April for the first time in five years. The video showed al-Baghdadi with a bushy gray and red beard and seated with a machine gun next to him. In December 2016, the U.S. State Department raised its reward to US$25 million for information on al-Baghdadi, making him one of the most wanted terrorists in the world. Born Ibrahim Awad al-Badri in 1971, the passionate football fan came from modest beginnings in Samarra, north of Baghdad. His high school results were not good enough for law school and his poor eyesight prevented him from joining the army, so he moved to the Baghdad district of Tobchi to study Islam. “He had a vision, early on, of where he wanted to go and what kind of organization he wanted to create,” said Sofia Amara, author of a 2017 documentary that unveiled exclusive documents on al-Baghdadi. After U.S.-led forces invaded Iraq in 2003, he founded his own insurgent organization but it never carried out major attacks. When he was arrested and held in a U.S. detention facility in southern Iraq in February 2004, he was still very much a second or third-tier jihadist. But it was Camp Bucca — later dubbed “the University of Jihad” — where Baghdadi came of age as a jihadist. “People there realized that this nobody, this shy guy was an astute strategist,” Amara said. He was released at the end of 2004 for lack of evidence. Iraqi security services arrested him twice subsequently, in 2007 and 2012, but let him go because they did not know who he was. In 2005, the father of five pledged allegiance to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the brutal leader of Iraq’s al-Qaida franchise. Zarqawi was killed by an American drone strike in 2006, and after his successor was also eliminated, al-Baghdadi took the helm in 2010. He revived the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), expanded into Syria in 2013 and declared independence from al-Qaida. In the following years, Baghdadi’s Islamic State group captured swathes of territory, set up a brutal system of government, and inspired thousands to join the “caliphate” from abroad. Uncharismatic and an average orator, al-Baghdadi was described by his repudiated ex-wife Saja al-Dulaimi, who now lives in Lebanon, as a “normal family man” who was good with children. He is thought to have had three wives in total; Iraqi Asma al-Kubaysi, Syrian Isra al-Qaysi and another spouse, more recently, from the Gulf. He has been accused of repeatedly raping girls and women he kept as “sex slaves,” including a pre-teen Yazidi girl and U.S. aid worker Kayla Mueller, who was subsequently killed. Al-Baghdadi’s death followed an international manhunt that consumed the intelligence services of multiple countries and spanned two American presidential administrations. Al-Baghdadi evaded capture for nearly a decade by hewing to a series of extreme security measures, even when meeting with his most-trusted associates. “They even made me remove my wristwatch,” recounted Ismail al-Ithawy, a top aide who was captured last year. He spoke from a jail in Iraq, where he has been sentenced to death. After being stripped of electronic devices, including cellphones and cameras, al-Ithawy and others recalled, they were blindfolded, loaded onto buses and driven for hours to an unknown location. When they were finally allowed to remove their blindfolds, they would find al-Baghdadi sitting before them. Meetings lasted between 15 and 30 minutes, and the ISIS chief would leave the building first. His visitors were required to stay under armed guard for hours after his exit. Then they were once again blindfolded and driven back to their original point of departure, according to aides who saw him in three of the past five years. “Al-Baghdadi’s concern was always: Who will betray him? He didn’t trust anyone,” said Gen. Yahya Rasool, a spokesman of the Iraqi Joint Operation Command. At its peak, ISIS controlled a territory the size of Britain from which it directed and inspired acts of terror in more than three dozen countries. ISIS once ruled over an estimated 10 million people in Iraq and Syria, enslaving women and performing public executions. Although its territorial caliphate ceased to exist earlier this year, there are still as many as 18,000 ISIS members in Iraq and Syria and Kurdish forces have said another 12,000 accused ISIS fighters were imprisoned. Acting under the orders of a “Delegated Committee” headed by al-Baghdadi, the group, known variously as ISIS, ISIL and Daesh, imposed its violent interpretation of Islam in these territories. Women accused of adultery were stoned to death, thieves had their hands hacked off and men who had defied the militants were beheaded. The ISIS also harnessed the Internet to connect with thousands of followers around the globe, making them feel as if they were virtual citizens of the caliphate. The message to these new jihadists was clear, and many of those on whose ears it fell found it emboldening: Anyone, anywhere, could act in the group’s name. That allowed ISIS to multiply its lethality by remotely inspiring attacks, carried out by men who had never set foot in a training camp.(SD-Agencies) |