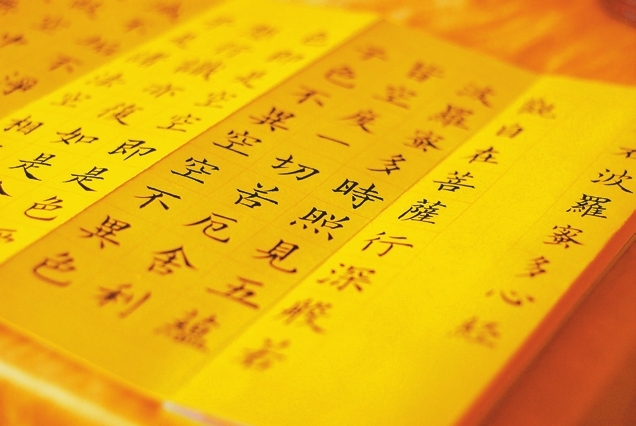

SUTRA copying was a hobby popular among the Qing (1644-1911) royals, as it was shown in palace dramas like “Empresses in the Palace” and hundreds of copies of various sutras written by Qing emperors kept in the Palace Museum. Known for its calligraphic merit, Emperor Kangxi’s copy of “The Heart Sutra” has even become one of the most sought-after copybooks sold on Tmall and JD.com, China’s two leading e-commerce platforms. Were the Qing emperor still alive, he would probably be more than surprised by the fact that an increasing number of modern urbanites are warming up to his hobby. Liu Fei, a 30-year-old white-collar worker in Beijing, bought a copybook of “The Heart Sutra” penned by Emperor Kangxi, published by the Palace Museum Press, months ago. A salesperson working for an online education company, Liu has been copying the sutra on and off for the past two years. “Aside from Emperor Kangxi’s work, I also followed calligrapher Zhao Mengfu’s (1254-1322) copies of ‘The Heart Sutra’ and ‘Tao Te Ching,’” Liu said. “They are all good choices for practicing the regular-script calligraphy.” Like Liu, many other calligraphy enthusiasts are also fond of copying classic texts of Buddhism, Taoism, and ancient poetry to enhance their handwriting. It can be largely explained by the fact that those canons were the common choices for renowned calligraphers in history. For example, Buddhist classic texts “The Heart Sutra” and “The Diamond Sutra,” Taoist classic “Tao Te Ching,” and classic poems such as “The Thousand-Character Text,” were most written by legendary calligraphers like Wang Xizhi (303-361), Liu Gongquan (778-865), Huang Tingjian (1045-1105) and Zhao Mengfu. Calligraphy, ranked as the supreme visual art form in traditional Chinese culture, has been considered by Chinese literati almost of all times, along with poetry as a means of self-expression and cultivation. In addition, the traditional belief — “zi ru qi ren,” meaning one’s handwriting can readily give away one’s true character, still has a strong foothold in the digital modern society. Aside from having one or two calligraphy classes at school, many primary schoolers are sent by parents to afterschool classes to further improve their handwriting, as it is widely held that neat, beautiful handwriting would probably earn the examinee bonus credits. Writing off stress and anxiety “Spending a day making phone calls to potential customers often leaves me drained at the end of the day and there seems to be buzz hovering in my head even after I get off work,” said Liu Fei, the saleswoman. “I usually spend about an hour focused on the copying before I go to bed. The quiet writing process helps me calm down and get the noise off my head so that I can get a good night’s sleep.” Whenever Liu completes a piece she thinks calligraphically meritorious, she would take a shot of it and post the photo on Sina Weibo, China’s Twitter equivalent. Usually she attaches a number of hashtags such as #PracticeCalligraphyTogether and #PowerOfHandwriting to her post, so that she can share her work with communities of like-minded people from around the country and beyond. Thumbing through the posts with these hashtags, it would be no hard to spot posts raving about what a stress-reducer calligraphy, or simply handwriting, is. “In this era of information explosion, everyone every day receives a plethora of information, mainly scraps of information, thus giving rise to a lot of stress and anxiety,” observed Li, a Guangzhou-based psychology professor who declined to give China Daily her full name. “Copying per se could easily become a simple, repetitive form of hand movements. But to make a decent copy requires one to write slowly and carefully so as to produce a flawless outcome. It is even more challenging to create a copy that is free of textual errors and at the same time visually appealing,” Li said. “Hence it’s a great way to keep people focused on what they do and therefore help reduce their anxieties.” Meanwhile, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to keep people’s lives in limbo, negative feelings such as boredom, panic and anxiety have spiked, as shown by the recent survey conducted by Beijing Normal University based on its Internet-and-hotline-based psychological assistance program launched to help the general public cope with psychological problems bred by the epidemic. To combat these negative feelings pent up inside, many more Chinese have elected to adopt calligraphy as a hobby during this troubled time to keep themselves busy while trying to tame the tiger locked up inside. The hashtag #WritingAtHome speaks volumes. Created by the official account of Weibo Calligraphy on Feb. 18, the online campaign has attracted a total of 6,148 original posts as of April 21, logging as many as 680 million reads. “Because of the epidemic, I’ve stayed at home for more than two months. Practicing calligraphy not only gets my handwriting improved, but affords me with a sense of fulfilment every day; otherwise I fear I’d fall sick merely from being cooped up at home for so long,” a Weibo blogger told China Daily in early April as to why she indulged in the online activity. An art of conscious living The boon of handwriting for boosting people’s mental wellbeing is also endorsed by mental health experts. “Writing with mindfulness is the key to helping people alleviate their anxiety,” noted Lin Chaihua, a psychology professor with Beijing Normal University. Many studies have shown mindfulness can help mitigate stress and anxieties as it means paying attention fully and nonjudgmentally to the present moment, said the professor. A practice rooted in Buddhism, Taoism, and yoga, mindfulness is described as “an art of conscious living” by Jon Kabat-Zinn, author of the 1994 book “Wherever You Go, There You Are,” a bestseller which helped catapulted mindfulness into mainstream in the West. Kabat-Zinn’s teacher, Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh, also practices calligraphy for mindfulness. Calling calligraphy meditation, he writes English words with a Chinese brush on rice paper, creating works that have been exhibited around the world for mindfulness promotion. Recent years have also seen modern English-language calligraphy, aka lettering in the West, garner millions of fans, thanks in part to the promotion of Megan, former Duchess of Sussex, whose stunning handwriting has sparked a widespread interest in the dying artform. The Megan Effect aside, lettering’s growing popularity more comes down to its magical healing power. Some Britons interviewed by the U.K. newspaper The Daily Mail in 2019 shared that lettering has helped them wrestle with parenting distress, chronic pain and even borderline personality disorder for guiding them into deep mediation and unlocking their creative side. Copying for inspiration, power Demanding the writer’s full attention to meticulously complete each stroke, copying classic texts is also traditionally deemed as one of the best ways to explore and ruminate on the wisdom crystalized in the classics. Wang Shaoqi, a calligraphy buff, adopted copying “Tao Te Ching,” a text of 5,284 characters, as a new hobby after he retired as a policeman in Qiqihar, Northeast China’s Heilongjiang Province. While copying, he liked to stop to ponder over the aphorisms in the work, such as “the movement of the Tao consists in returning, and the use of the Tao consists in softness,” Wang told a local media outlet in 2018. “The reason why I enjoy copying the classic so much is that it helps the values in this ancient classic sink in and thus offers me new thoughts on life and the world,” the retiree beamed. For Bai Ruyun, a 45-year-old farmer from North China’s Hebei Province, copying ancient Chinese poems saved her from a close brush with death while she was in a years-long battle against lymphoma, as she revealed in a poetry-related variety show in 2017. After being diagnosed with the cancer in 2011, Bai went through chemo several times. During those hospitalized days, she started reading ancient Chinese poetry and copied them into her notebook with essential notes for better understanding. Through taking a leaf from poets like Tao Yuanming (365-427), Li Bai (701-762) and Su Dongpo (1037-1101) whose poems show their calmness, resilience, and optimism in their eventful lives, Bai endured the pains of chemotherapy treatments and finally won the bitter battle. “With a backward glance at the windswept place, I carry on, in spite of wind, rain or shine,” Bai quoted one of Su Dongpo’s famous verses in an interview, adding, “Reading and copying those inspiring verses is like a ferry that helped carry me through the hard times.” (China Daily) |