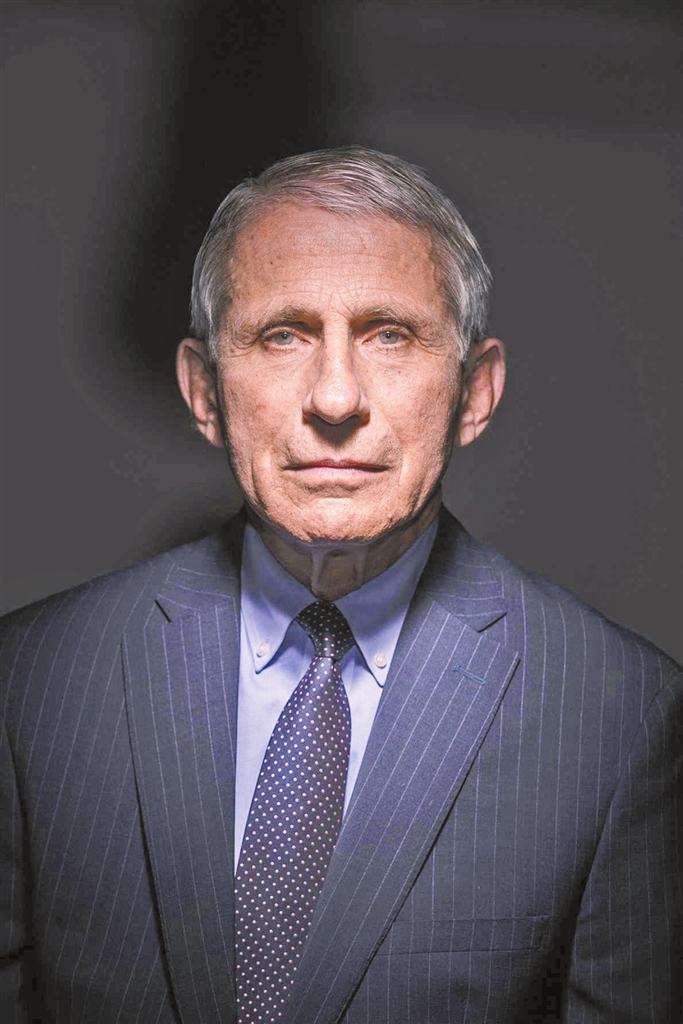

THE United States’ top infectious diseases expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci, said Monday that there is “no scientific evidence” to point to the novel coronavirus having been manufactured in a Chinese laboratory. In an interview in National Geographic, the director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), who has been one of the leading medical experts helping to guide the U.S. response to the highly contagious COVID-19 that has swept across the world, rubbished suggestions that the virus was created at a facility in Wuhan — insisting COVID-19 is naturally occurring and has not been “deliberately manipulated.” “If you look at the evolution of the virus in bats and what’s out there now, [the scientific evidence] is very, very strongly leaning toward this could not have been artificially or deliberately manipulated,” Fauci said. “Everything about the stepwise evolution over time strongly indicates that [this virus] evolved in nature and then jumped species.” Based on the scientific evidence, he also doesn’t entertain an alternate theory — that someone found the coronavirus in the wild, brought it to a lab, and then it accidentally escaped. For decades, Fauci has been known as the hardest worker in Building 31 — the first scientist to arrive at the sprawling National Institutes of Health campus in Bethesda, Maryland, in the morning and the last to leave in the evening. “He’s even found notes on his windshield left by co-workers that say things like, ‘Go home. You’re making me feel guilty,’” U.S. President George W. Bush said in 2008 when he awarded Fauci the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In the last month, the 79-year-old infectious disease expert’s schedule has gotten more grueling as he works on the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic: squeezing in three to five hours of sleep between supervising work on a potential vaccine, making hospital rounds, attending meetings of the coronavirus task force and speaking at White House news conferences. The frank and straight-shooting New Yorker, who has led U.S.’ response to every major epidemic since the outbreak of AIDS in the 1980s, has been striving to ensure the science conveyed to the public is clear and accurate. As millions of Americans turn to him during the coronavirus pandemic, the physician-scientist has had to acquire a new skill: The art of delicately pushing back against the bluster of his boss, President Donald Trump, without saying he’s wrong. Both men are in their 70s and both are proud of their New York upbringing — but that’s about where the similarities end. With his calm, professorial demeanor, pint-sized Fauci is fast becoming a household name as the evidence-driven straight shooter in the administration’s coronavirus task force. During a televised meeting with pharmaceutical executives in early March, Trump — who before he became president was famously skeptical of vaccines — appeared to suggest one could be delivered to start immunizing the public against the virus in “three to four months.” “You won’t have a vaccine, you’ll have a vaccine to go into testing,” replied Fauci in the gravelly Brooklyn accent now familiar to the U.S. public. “Like I’ve been telling you, Mr. President, a year to a year and a half,” he added, spelling out a more realistic timeline for clinical trials to determine a vaccine has a sound scientific basis, is safe, and can be scaled. More recently Fauci has been tempering expectations about the prospects of anti-malarial drugs hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, which Trump earlier hailed as a “game changer” after the medicines showed early promise in small-scale studies in France and China. Asked a day later whether he agreed, Fauci stressed it was too early to say and that any “anecdotal evidence” still needs validation in randomized clinical trials. Fauci, for his part, has consistently downplayed these public yet polite disagreements, telling the respected Science magazine that he and Trump were largely in agreement on substance but mainly differed in emphasis. “The next time they sit down with him and talk about what he’s going to say, they will say, by the way, Mr. President, be careful about this and don’t say that,” he said. “But I can’t jump in front of the microphone and push him down.” Born to Italian-American parents in Brooklyn, Fauci was drawn to health care because of his father, who was a pharmacist. He joined the National Institutes of Health (NIH) — the taxpayer-funded steward of medical and behavioral research — in 1968, two years after receiving his medical degree from Cornell University, and began his career working on immune diseases. In 1981, Fauci was a senior investigator with NIAID when he read reports about gay men suffering from immuno-compromised forms of pneumonia and cancer — and he was struck with a shocking realization. At the time, he was one of the few researchers devoted solely to human infectious diseases. Most young scientists were told that the field was a dead end after the conquering of polio and tuberculosis. “I actually remember getting goose pimples about it, because I’m saying, ‘Oh my goodness, this is a new disease,’” he said in a 2011 interview. Recognizing early on that the new illness could be a global disaster, Fauci assembled a small group of scientists to study the emerging disease and devoted his whole lab to AIDS research. In 1984, he was appointed director of the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a position he holds to this day, having refused the role of NIH director four times under different presidents. Since then, the veteran scientist and HIV/AIDS researcher has spearheaded the nation’s approach to preventing, diagnosing and treating epidemics for nearly four decades, advising six U.S. presidents. During the 1980s, he became a lightning rod for criticism that the government was not doing enough to stem the rise of HIV-AIDS — but rather than run from activists he took their views on board, a collaboration he told The Lancet was key. His accomplishments include implementing a fast-track system that widened access to anti-retroviral medicines, and working with former President George H. W. Bush to plough in more resources. As a clinician, Fauci made significant breakthroughs in understanding how HIV destroys the body’s immune system and helped develop strategies to bolster immune defenses. Under President George W. Bush, Fauci was the architect of the President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief, which focused on combatting the disease in Africa and other parts of the developing world upon its launch in 2003. Following his experiences as the government face of AIDS research, Fauci reappeared for the public health threats that marked successive administrations, including the West Nile virus under President Bill Clinton; the anthrax scare and SARS under Bush; and the swine flu pandemic under Barack Obama. He received the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his work on AIDS in 2008 and more recently has overseen the U.S. response to the Zika virus and Ebola. He also demonstrated an empathetic human touch when Ebola surfaced in 2014, famously hugging an American nurse who had recovered from the disease before traveling to the heart of the outbreak in Liberia for large-scale clinical trials of vaccines. Fauci is credited with developing effective treatments for formerly fatal inflammatory diseases, as well as for contributions into understanding how HIV destroys the body’s defenses. And in addition to overseeing his own lab, he continues to treat patients at the NIH’s Clinical Center in Bethesda. For his current efforts, Fauci has been widely hailed as an “American hero” and a “national treasure,” even as he refuses, as many Democrats might like, to criticize Trump more forcefully over what they see as the president’s early reluctance to take major actions. Instead he likens the current scenario to a “fog of war” and consistently discourages Monday morning quarterbacking, or unfair criticism with the benefit of hindsight. “I don’t want to act like a tough guy, like I stood up to the president,” he told New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd. “I just want to get the facts out. And instead of saying, ‘You’re wrong,’ all you need to do is continually talk about what the data are and what the evidence is.” (SD-Agencies) |