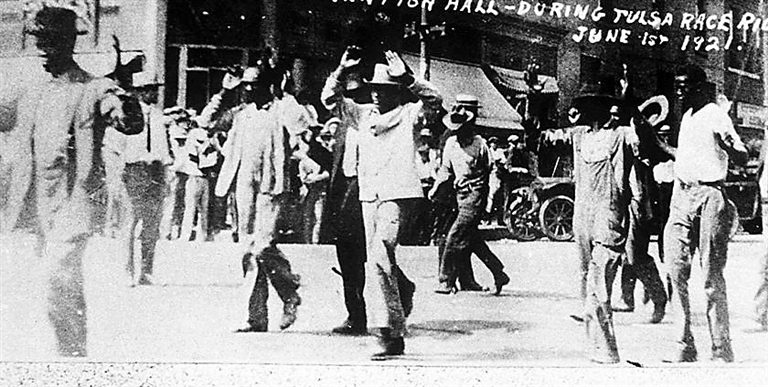

A 105-YEAR-OLD survivor of the 1921 race massacre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the United States, is the lead figure in a lawsuit that demands reparations for damage it says has continued since the destruction of the city’s Black business district. Lessie Benningfield “Mother” Randle was a little girl when an angry white mob rampaged through the city’s Greenwood District, known as “Black Wall Street” because it was home to more than 300 Black-owned businesses. By the end of the night June 1, 1921, the 35-city block district was burned to the ground. Contemporary reports of deaths began at 36, but historians now believe as many as 300 people died, according to the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum. The lawsuit was filed Tuesday in Tulsa County District Court by Justice for Greenwood Advocates, a team of civil and human rights lawyers. The plaintiffs include Vernon A.M.E Church — the only Black-owned building to survive the massacre — descendants of other victims and the Tulsa African Ancestral Society. The lawsuit claims that the racial and economic disparities caused by the massacre created a public nuisance and an economic blight that remains. It says local government and agencies failed to help the neighborhood rebuild. “Greenwood and North Tulsa Community residents continue to face racially disparate treatment and barriers to basic human needs, including jobs, financial security, education, housing, justice, and health,” it says. The state of Oklahoma used the public nuisance law to win a US$572 million lawsuit against drugmaker Johnson & Johnson last year for its role in the state’s opioid crisis. According to the lawsuit, the mob looted and destroyed Randle’s grandmother’s home, causing her “emotional and physical distress that continues to this day.” “She experiences flashbacks of Black bodies that were stacked up on the street as her neighborhood was burning, causing her to constantly relive the terror of May 31 and June 1, 1921,” the lawsuit said. Randle is one of the last living survivors of the massacre, which occurred after a 19-year-old Black man, Dick Rowland, was accused of assaulting a 17-year-old white girl named Sarah Page in the elevator of a Tulsa building. Charges against Rowland were later dismissed, according to the Tulsa Historical Society. Attorney Damario Solomon Simmons said Randle is in poor health but was “upbeat and encouraged” when she heard about the lawsuit. The plaintiffs contend that members of the Tulsa Police Department, the Tulsa County Sheriff’s Department and the Oklahoma National Guard participated in the mob. It said the National Guard provided tactical and logistical support to the mob. The Oklahoma National Guard, in a statement, defended its actions at the time. “The historical record shows that a handful of Guardsmen protected the Tulsa armory and the weapons inside from more than 300 rioters. The actions of these Guardsmen substantially reduced the number of deaths in the Greenwood District. In the days following the riots, Oklahoma Guardsmen restored order to the area and prevented further attacks by both black and white Tulsans.” The lawsuit says that Greenwood residents suffered US$50 million to US$100 million in property damage from the massacre and says that policies implemented in the following decades led to the decline of Greenwood and North Tulsa and increased inequality. It does not ask for a specific dollar amount in reparations, but calls for victims to be compensated for their lost property and the money that should have gone to the community since 1921. The lawsuit calls for the creation of a victim compensation fund, mental health and education programs for residents of Greenwood and North Tulsa and a college fund for descendants of massacre victims. It seeks construction of a hospital in the community and asks that Black residents from the Greenwood and North Tulsa communities to have priority consideration for city contracts. “Ms. Randle has been hurting all these years by what happened in Tulsa. It’s been a huge burden on her and she believes it’s about time for the city to pay what’s owed,” Solomon-Simmons said. “Ms. Randle wants respect, restoration and repair from the City of Tulsa.” In the years before the massacre, Greenwood was known in the early 1920s as a beacon of Black prosperity in the nation. With doctor’s offices, hospitals, lawyers, shops and newspapers, it was virtually self-sustainable and distinct from white Tulsa, south of the train tracks. Mary E. Jones Parrish, a Black woman who gave a written, first-hand account of the massacre, called it “a city within a city.” The success and wealth of this Black community, however, made poor white people in the neighboring areas envious and resentful, historians say. Tensions boiled over when Page accused Rowland of assaulting her in an elevator. Page worked as the elevator operator, and Rowland would frequently use the elevator because he had been given special permission to use the restroom and drink water in the building. Rowland was arrested and soon there was a rumor spreading that Page had been raped. An angry white mob showed up at the jail with the intent to lynch Rowland. A group of African Americans, many of whom had just served in WWI, came to the jail to defend Rowland, whom they believed was innocent. Outside of the jail, there was a struggle over a gun and shots went off. Chaos ensued. On May 31, 1921, thousands of white Tulsans, 2,000 of whom were deputized by the police, stormed the Greenwood neighborhood. The attack ended with hundreds of Black lives lost, an entire neighborhood burned to the ground, and thousands left without homes. In one day and night, the nation’s most prosperous black community was reduced to rubble. Hundreds were killed, more than 2,000 business were destroyed, and over 10,000 Black Tulsans were left injured, homeless and destitute. Bodies were buried by strangers in mass graves, whose families were never told whether their loved ones died or where they were buried, Scott Ellsworth, a University of Michigan historian who has long worked on the recovery of Tulsa massacre graves, said. For decades, the massacre — often referred to as the Tulsa race riots — was largely unacknowledged. The massacre has gotten more attention in recent years, particularly on its 99th anniversary in June this year, which occurred amid nationwide protests over racial injustice following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Nearly 100 years later, Tulsa is still suffering from the legacy of that violence and racism. In the segregated city, more than 33 percent of residents in predominantly Black North Tulsa live in poverty compared with less than 14 percent of residents in South Tulsa. Black Tulsans are subjected to police violence — such as the use of tasers and pepper spray — 2.7 times more than whites, according to Human Rights Watch. For the African American community, the Greenwood massacre isn’t just history — it is felt to this day. Tulsa’s Black residents say they have spent decades seeking justice that they still have not received and there is still a reluctance — especially among white residents — to fully acknowledge the events of 1921.(SD-Agencies) |