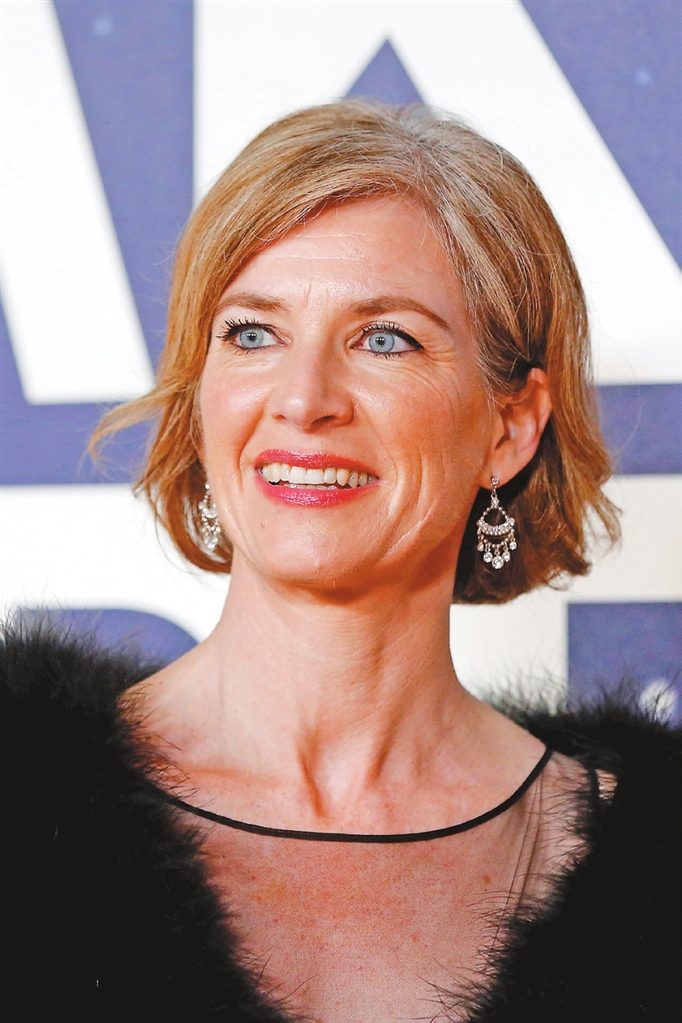

THE 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry has been awarded to two scientists for developing a gene-editing tool. French scientist Emmanuelle Charpentier, director of the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens in Berlin, and American biochemist Jennifer A. Doudna, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, are the first two women to ever share the prize in its 119-year history. It takes the total number of women who have won a Nobel prize up from five to seven. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announced Wednesday that Charpentier and Doudna were awarded the prize for developing the CRISPR/Cas9 genetic scissors. The prestigious award comes with a gold medal and prize money of US$1.1 million courtesy of a bequest left more than a century ago by the prize’s creator, Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel. “Using these, researchers can change the DNA of animals, plants and microorganisms with extremely high precision,” says a press release by the academy. “This technology has had a revolutionary impact on the life sciences, is contributing to new cancer therapies and may make the dream of curing inherited diseases come true.” The academy says since the women discovered the CRISPR/Cas9 genetic scissors in 2012 their use has exploded and has lead to other important discoveries. It could help get rid of diseases like cystic fibrosis, muscular dystrophy and even HIV and cancer. Using the CRISPR/Cas9 genetic scissors made once time-consuming and sometimes impossible work easier and “it is now possible to change the code of life over the course of a few weeks,” the press release reads. Thanks to the scissors, clinical trials of new cancer therapies are now under way. “There is enormous power in this genetic tool, which affects us all,” Claes Gustafsson, chair of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, said. “It has not only revolutionized basic science, but also resulted in innovative crops and will lead to ground-breaking new medical treatments.” Charpentier unexpectedly discovered a previously unknown molecule, tracrRNA, and after publishing her discovery in 2011 she began collaborating with Doudna. Together, they discovered the CRISPR/Cas9 genetic scissors. “Very surprised!” said Charpentier in an on-site telephone interview, adding that the CRISPR/Cas9 genetic scissors “have the opportunity to develop therapeutics to defeat bacteria.” “I am overwhelmed and deeply honored to receive a prize of such high distinction and look forward to video-celebrating this exceptional award with my team members, colleagues, family and friends. My special thoughts go to my former lab members — especially Elitza Deltcheva and Krzysztof Chylinski — who have contributed significantly to the deciphering of the CRISPR/Cas9 mechanism in bacteria and my colleagues of the field of CRISPR biology. This award obviously underlines the importance and relevance of fundamental research in the field of microbiology.” She added that as a female scientist, she was very happy to get the prize and wanted to send a “strong message to young girls who would like to follow the path of science, and to show them that women in science can also be awarded [Nobel] prizes.” Doudna, the first woman on the UC Berkeley faculty to win the coveted award and the campus’ 25th Nobel laureate, said in a news release Wednesday that the technology gives new hope and possibility to society. “Many women think that, no matter what they do, their work will never be recognized the way it would be if they were a man,” said Doudna, adding that the prize made a strong statement that “women can do science, women can do chemistry.” “This great honor recognizes the history of CRISPR and the collaborative story of harnessing it into a profoundly powerful engineering technology that gives new hope and possibility to our society,” said Doudna. “What started as a curiosity-driven, fundamental discovery project has now become the breakthrough strategy used by countless researchers working to help improve the human condition.” “I encourage continued support of fundamental science as well as public discourse about the ethical uses and responsible regulation of CRISPR technology,” she added. CRISPR/Cas9 is one of the biggest discoveries of the 21st century. Since it was developed in 2012, this gene- editing tool has revolutionized biology research, making it easier to study disease and faster to discover drugs. The technology is also significantly impacting the development of crops, foods and industrial fermentation processes. But the one application that has made it famous is the modification of the human genome, which brings the promise of using CRISPR to cure diseases. CRISPR stands for Clustered Regularly Interspersed Short Palindromic Repeats. The term makes reference to a series of repetitive patterns in the DNA of bacteria and archaea that were extensively researched by Spanish scientist Francis Mojica in the 1990s. These patterns are the basis of a primitive immune system that bacteria use to “remember” the DNA of viral invaders by incorporating the DNA sequence of the virus within the CRISPR patterns. The Cas9 protein is then able to recognize the DNA sequence stored within CRISPR patterns and cut any DNA molecules with a matching sequence. But it wasn’t until 2012 that Doudna and Charpentier took the discovery a step further and proposed that CRISPR/Cas9 could be used to cut any desired DNA sequence by just providing it with the right template. In theory, CRISPR gene editing could be used to make any modification to the DNA of virtually any living being. In biotech and pharma companies, CRISPR is becoming the go-to tool for drug discovery. In academic research labs, the gene-editing tool is being used to modify the genome of all sorts of organisms to study the function of any gene of interest, whether it is one that causes disease or one that makes a crop grow faster or survive harsh conditions. In agriculture, CRISPR could be used to produce crops with better yields or that resist drought, much faster than is possible with traditional breeding techniques. It can also be used to add new features, such as making tomatoes spicy, or remove others — for example making gluten-free wheat or decaf coffee beans. However, regulations can limit the use of these technologies. While the U.S. has already seen the launch of CRISPR-modified crops, the European Union decided to set strict GMO regulations that scientists believe are hindering the potential of the technology. But right now, most of the money seems to be in using CRISPR/Cas9 to engineer human DNA. With over 10,000 diseases caused by mutations in a single human gene, CRISPR offers hope to cure all of them by repairing any genetic error behind them. The breakthrough research done by Charpentier and Doudna was only published in 2012, making the discovery very recent compared to many Nobel wins that are often only honored after decades have passed. Charpentier, born in 1968 in France, got her Ph.D. in 1995 from Institut Pasteur, Paris. She is considered a world-leading expert in regulatory mechanisms underlying processes of infection and immunity in bacterial pathogens. In 2012, she co-discovered CRISPR and went on to cofound the drug-discovery business CRISPR Therapeutics and the intellectual property firm ERS Genomics. CRISPR Therapeutics has raised over US$500 million. It is valued at around US$2.5 billion, and has offices in the U.S., Switzerland and the U.K. Charpentier is now establishing her own research unit at the esteemed Max Planck Society in Berlin, Germany. Doudna, born in 1964 in Washington, D.C., got her Ph.D. in 1989 from Harvard Medical School. She is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and an investigator at Howard Hughes Medical Institute. In 2016, she and Charpentier were among five recipients of Warren Alpert prize for CRISPR research. That year, Doudna told a Harvard symposium the medical school was her “scientific home.” “Fundamental, curiosity-driven research is really what underscored and made possible the evolution of this technology,” she said. “It’s exciting and certainly a principle I learned as a student here.”(SD-Agencies) |