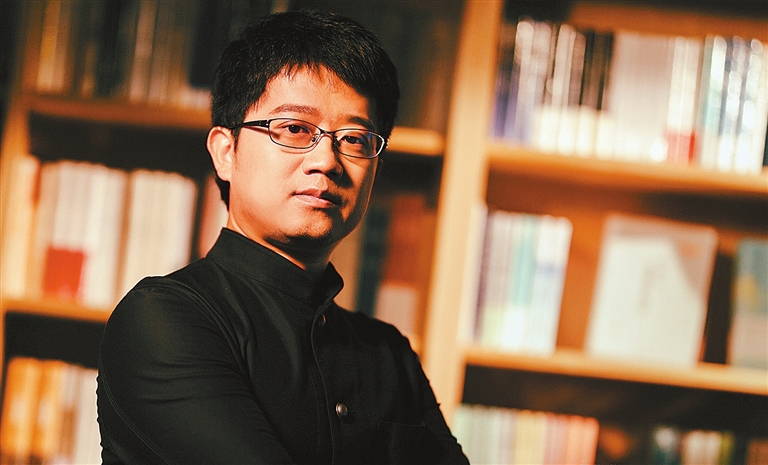

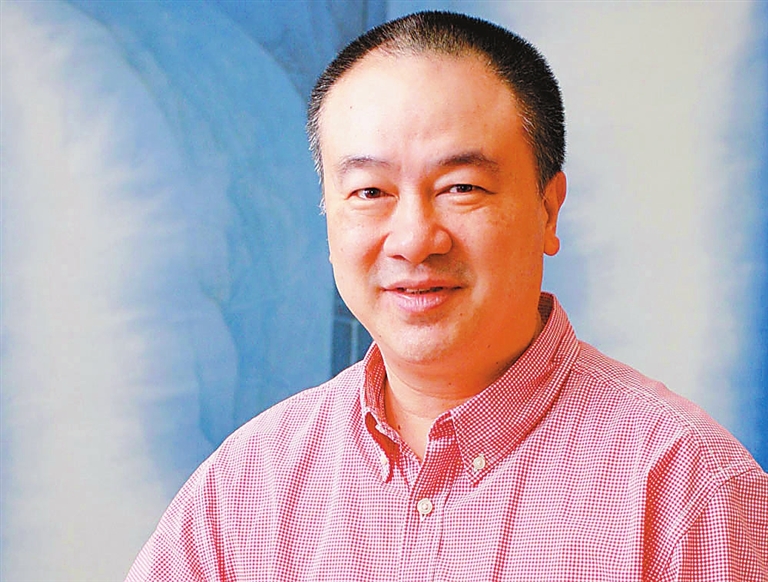

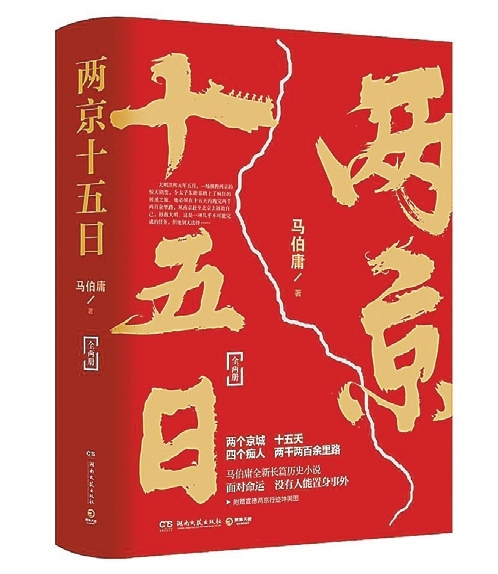

CHINESE mainland writer Ma Boyong’s highly acclaimed novel “Fifteen Days Between Two Capitals” will be turned into a stage drama by Hong Kong movie and stage director Clifton Ko later this year, according to a news release by CPAA Theaters in Beijing. Historical events in 1424 have provided a surprising backdrop to the 584-page Chinese novel that is attracting a large readership. That year, decades before Christopher Columbus was born, saw a number of earthquakes strike Nanjing which, a few years earlier, had been the capital of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Emperor Zhu Gaozhi sent his son, crown prince Zhu Zhanji, from the current capital, Beijing, to Nanjing to record the extent of the damage and provide comfort and practical aid to the populace. Later that year, in the middle of the fifth lunar month, the emperor fell severely ill and he sent officials to inform the prince to come back to inherit the throne. This is where, as they say, the plot thickens. The ruler’s younger brother Zhu Gaoxu coveted the seat of supreme power and organized an ambush to attack his nephew, the crown prince. However, Zhu Gaoxu failed and Zhu Zhanji returned safely on the third day of the sixth lunar month to claim the throne. When writer Ma, 40, read about the historical incident, from the official Ming section of “Twenty-Four Histories,” he was amazed to find that fewer than 100 Chinese characters were written about the episode. His interest was aroused and he had an overwhelming urge to write a thriller. “The historical document only tells us the time and the result without providing any other clues, so it leaves plenty of room for my imagination,” says Ma. While based on actual historical facts, Ma chronicles, with literary license, the crown prince Zhu Zhanji’s adventure from Nanjing to Beijing over the period of 15 days. It sees the young royal face moments of extreme peril as his uncle attempts to silence him, but he finally reaches the capital with the help of officials Yu Qian, Wu Dingyuan and doctor Su Jingxi. “When I read the historical record, I noticed that the means of transport Zhu used was not mentioned, but he managed to come back to Beijing in a relatively short time. After much calculation, I inferred that he may not have ridden a horse home, since that might make him miss the transfer of power,” Ma says. “So, taking ships along the Grand Canal between Beijing and Hangzhou would be a possible choice.” The idea inspired the writer to make the Grand Canal a key part of his novel, an actual real-world game of thrones. He depicts vivid scenes along the canal with a clarity that suggests that he personally witnessed them minutes before putting pen to paper. “I always try to find a foundation in traditional Chinese culture, for my novels,” Ma explains. “By making the prince rush along the Grand Canal, I can depict life along the historic waterway at that time, and its influence on China’s culture, economy and politics during the Ming Dynasty.” The author noticed that most of the existing novels and documentaries about the Grand Canal have a tendency to highlight themes from lyrical, idyllic perspectives. However, he was more amazed by the detail and creativity in the construction of the canal. “It was much more sophisticated than I had imagined,” Ma says. Ma, who graduated from the University of Waikato in New Zealand with a master’s degree in marketing, has an uncanny ability to describe technical details in a way that draws the reader in. In order to learn more background information, Ma read a large number of historical documents and went on many fact-finding field trips to sites along the canal. He also consulted numerous experts to understand the technical details and turn these into everyday language. His hard work has paid dividends, and won wide acclaim among many young followers, who said they were drawn in by the vivid historical scenarios. This is epitomized in a comment by a Douban user posting under the name Liuxizi: “Ma links many historical facts and ancient systems in ‘Fifteen Days Between Two Capitals,’ just like showing a long painting of the Grand Canal during the early Ming Dynasty. I used to find it difficult to learn about history by reading academic books, but this book gives me an impression of the vivid society during the Ming Dynasty.” In a historical novel, reality and fiction coexist. In Ma’s book, he makes sure that historical facts are kept intact, but Ma does “fabricate other matters, such as the creation of fictional characters in the novel.” As well as the fictional ensemble, Ma also elevates patriotic official Yu Qian to one of the main characters of his tale. Yu would later play an important role in leading the defense of the Ming capital, Beijing, from attacks by the Oirat Mongols. “We all know that Yu is a national hero, but his early experience is rarely mentioned in historical documents,” says Ma. “So I tried to imagine Yu’s earlier experiences in life that would help shape his future destiny.” After his book was published in July, the fictitious historical novel has achieved a solid 8.2 score out of 10 on China’s popular review site Douban. More than 1 million copies of the thriller have been sold so far, according to the Hunan Literature and Art Publishing House. “There are lots of twists and turns in the novel; since I will turn it into a two-hour stage drama, I will select the most intriguing parts from it,” said director Ko. “Meanwhile, I will make this stage production movie-like to give it more tension.” Ma, from Chifeng, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, has a pretty enviable track record in writing popular history-based thrillers. Last year, his 637-page book “The Longest Day in Chang’an” was adapted into a popular TV series. It took viewers to the heyday of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). On the Chinese social media Weibo, Ma has 7.78 million followers. He is skillful in writing historical fiction and has published many popular books, some of which have been translated into Japanese, Thai and Korean. Ma has earned the nickname “prince” among his enthusiastic followers, yet his sense of commonality is reflected in his works. He says that, although historical novels depict the past, they can still be relevant to modern life. “In ancient China, for example, people paid a great deal of attention to social hierarchy, and often ignored people from the lower classes,” says Ma. “But in modern times we stress people’s equality, so we can view history from the angle of each person’s value. “In present society, we are all members of the general public, so when we see the struggles of the ordinary people in ancient history, we often develop an emotional connection with them, and would like to learn their stories.” According to CPAA Theaters, Ko’s stage drama is scheduled to debut in Beijing in October and then tour to other Chinese cities, including Hong Kong. Ko entered the Hong Kong TV and film industry in the late 1970s and directed his first film “The Happy Ghost” in 1984. The film, like all his major works, is a slapstick comedy with moral teaching, family value and optimism. Ko was prolific in making family-themed comedy movies in the 1980s and 1990s, such as “It’s a Mad, Mad and Mad World” and “All’s Well, Ends Well.” In recent years, he mainly engages in directing stage dramas. (SD-China Daily) |