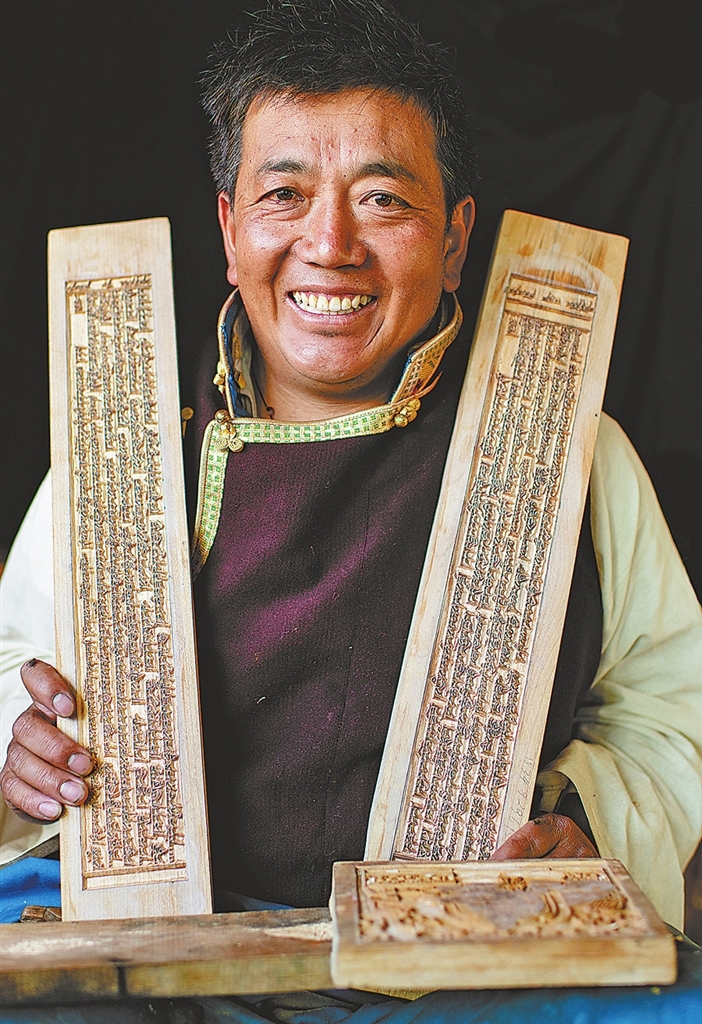

NYEMO, a culturally rich county in the Tibetan Autonomous Region, is known for three intangible heritage handicrafts: Tibetan incense, handmade paper and hand-engraving. Local villagers are embracing a better life with their expertise as they preserve and pass on the handicraft talents. In the Tibet Autonomous Region, wherever you visit temples or homes, you immediately notice a special smell that fills every corner. This comes from Tibetan incense, made from the cypress tree. The wood is ground into pulp in a water mill; after drying the pulp is made into incense bricks. These in turn are ground into powder and mixed with saffron, musk, sandalwood and other medicinal herbs and spices, and then squeezed with ox horns. Pressed into strips and dried, the finished product is ready for use. This technique has been handed down through thousands of years. Nyemo is the hometown of Thonmi Sambhota, a Tibetan incense specialist. Tibetan paper, too, owes its existence to exquisite and ancient craftsmanship. The transformation from the original raw material to a collection of books that carry the Tibetan history and culture for thousands of years, without any modern machinery being involved, is a generous gift of nature and its secret is part of the wisdom of the Tibetan people. With a history of more than 1,300 years, the paper is still made via traditional handmade techniques. Its special raw material and formula have given the product extreme longevity. In Tibet, many classics of literature and history are printed on Nyemo Tibetan paper, which after more than a thousand years are well preserved and fully intact. Nyemo Tibetan paper has recorded the history of Tibet and witnessed the progress of Tibet’s civilization. The raw material for making Tibetan paper is wolfsbane. Every year in July, this type of poisonous grass will see a bloom of beautiful flowers. But their beauty conceals lurking danger; they are highly toxic, so that cattle and sheep will avoid it when they see it. This makes the paper made of the wolfsbane plant “invulnerable to all insects.” People in Nyemo call this grass, which grows in grasslands and alpine meadows, “paper clips.” This grass is inconspicuous in the bush when not blooming, but it is easily recognizable with beautiful flowers. The grass grows up to 1 meter tall and bears a cylindrical flower ball; the outside of the blossom is white, and the center is pink or purple. The papermaking process includes picking, soaking, washing, mashing, peeling, tearing, cooking, beating, pouring, drying, peeling and finally calendaring by squeezing the product through various sized rolls. The origins of the Pusum hand-engraving technique can be traced back to the seventh century. Legend says the 32nd generation Songtsen Gampo of the Tubo Dynasty came to Lhasa Valley on a journey to find the site for his capital city. When the king stopped to bathe in the river, he saw the sun refracting on the rock to reveal the six-character mantra, so he asked Nepalese craftsmen to engrave a Buddha statue on the rock, and then built the capital there. Since then, stone carving has become the most common form of artistic expression in Tibet, and Pusum hand-engraving evolved from it. Now the ancient craft is lost elsewhere, except in PusumTownship where craftsmen still do it. Today, most of the handicrafts are engraved wood panels. Pusum hand-engraving involves meticulous handwork, exquisite craftsmanship and complicated processes. From wood selection and carvingto stringent quality checks, there are more than 30 processes before a high-quality woodblock is ready, all of which are done manually. The carving knives are also extraordinary. Each craftsman has his own set of special carving knives, usually more than 20. Pusum hand-engraving has various forms. Not only are there text and pattern carvings, but they are also widely used in the printing of prayer flags.(China Daily) |