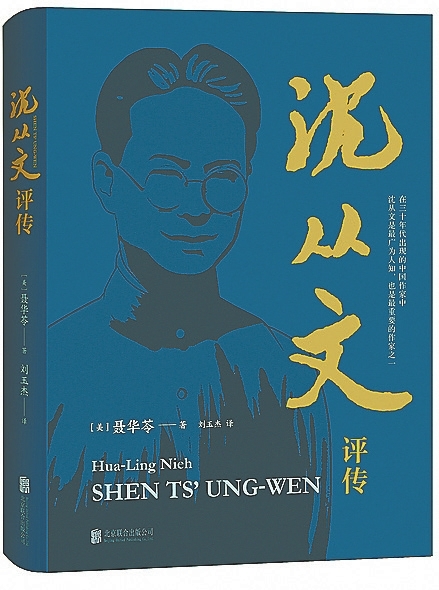

HALF a century after Chinese-American writer Nieh Hua-ling’s monograph “Shen Ts’ung-wen” was published in the United States, a Chinese version has finally been released domestically at the beginning of this year. Nieh’s work, published in 1972, was the first of its kind to introduce Shen Congwen (1903-1988), or Shen Ts’ung-wen, to the English-language world. Shen was one of the most influential modern Chinese writers. Late Swedish Sinologist Goran Malmqvist (1924-2019) of the Swedish Academy, a member of the selection panel of the Nobel Prize for Literature since 1985, once confirmed, despite the 50-year secrecy rule, that Shen was heavily tipped to win in 1988 but passed away before selection. In the book, from the New York-based publisher Twayne’s World Authors Series, Nieh reviews Shen’s early life and paints a larger picture of the backdrop to China’s revolution, as well as the literary and political activities of intellectuals at the time. She highlights the artistic quality of Shen’s works and notes that he was a writer “who waded through mankind’s misery to get to its basic humanity,” and who “wrote with classic simplicity, struggling to match the right words to his noble passions.” Many of Shen’s representative works, such as the novella “Border Town” and collection of essays “Xiangxi,” depict the landscape and culture of his hometown in Fenghuang County in Central China’s Hunan Province. It is located in the west of the province, a mountainous region known as Xiangxi. His home, located in Fenghuang ancient town, has become a travel hot spot with many visitors drawn to it by Shen’s words. Fenghuang is a water town with wooden, stilted buildings standing sentinel alongside a meandering river. Nieh’s words reveal that Shen didn’t attend school much and spent a long time in the army in the early years of his life before taking up, almost incongruously considering this background, a position as a literature editor for various newspapers and magazines before becoming a university lecturer on literary history. He set up residence in several cities around the country. In childhood, he liked to play truant, spending time in the fields or lingering on the street, observing people, from all walks of life. Such panoramic observation provided him with abundant material for writing, as his works include people from a comprehensive social milieu. Recognizing his connections to rural life, Shen presented delicate writing on the beauty of the countryside and people of virtue and kindness leading a life close to nature. He once wrote that water played an important role in forming his outlook on appreciating beauty and learning how to think. He explained that, for many stories, the background pictures, personalities, language styles and the melancholy temperament that he adopted in his writing had been inspired by observations of water. In “Border Town,” a love story about a boatman’s granddaughter Cuicui, Shen displays an almost ideal world in the countryside, where the virtues of human nature are presented to the extreme, while giving an “impressionist” — as Nieh has put it — depiction of the landscape, the town, local customs and the people. The novella was first translated into English by journalist and author Emily Haan from the United States and Chinese writer Shao Xunmei as early as in 1936, two years after its publication, followed by several other translated versions over the decades. However, having experienced violence and ideological upheaval during the first half of his life, Shen didn’t shy away from showing the dark side of human nature, and also expressed a reluctance to embrace the modern life that he thought had alienated human nature. Shen rarely wrote in the latter half of his life, but devoted himself to researching cultural relics at what is now the National Museum of China, especially ancient silk patterns, bronze mirrors and porcelain. His “Study of Ancient Chinese Clothing and Ornaments,” published in 1981 in Hong Kong, was a great contribution to the history of Chinese materials. It was not until the 1980s that Shen’s literary works were rediscovered and his position in modern Chinese literary history reevaluated. Research on his works has boomed since then. Nieh was born in 1925 in Wuhan, Hubei Province, and went to Taiwan with her family in 1949 before immigrating to the U.S. to attend the Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa in 1964. Apart from her own writings that have achieved global acclaim, represented by “Mulberry and Peach: Two Women of China,” she was known for co-founding the International Writing Program at the university with her late husband Paul Engle (1908-91). Over 1,500 writers from more than 150 countries and regions have attended the program over the past five decades. Dozens of authors active in the Chinese literary scene have joined the program. And, in 1976, around 300 writers nominated the Engles for the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1964, when Nieh left Taiwan for Iowa City in the U.S., the only book she took with her was Shen’s collection of essays, “Sketches of a Trip to Hunan.” And, in her book, Nieh recounts the interactions when the Engles finally met Shen in person in Beijing in 1980 and 1984. In Nieh’s mind, it takes all the senses — visual, tactile, olfactory and gustatory — to appreciate Shen’s words. He had a wealth of imagination and different styles of writing. Nieh went to the U.S. in the 1960s and returned to China only a few times. Her influence in domestic literary circles was not as great as it was overseas, according to Xiao Yao, one of the editors of the Chinese version of “Shen Ts’ung-wen.” In a time of limited cultural exchanges, the author and the publisher did not vigorously promote the publication of different language versions of the book, and this, Xiao explains, is why it took 50 years to publish a Chinese version. “There are not many biographies about Shen in China. I believe this one will help readers know more about his life and personality and have a deeper understanding of the beauty and artistry of his work.”(China Daily) |