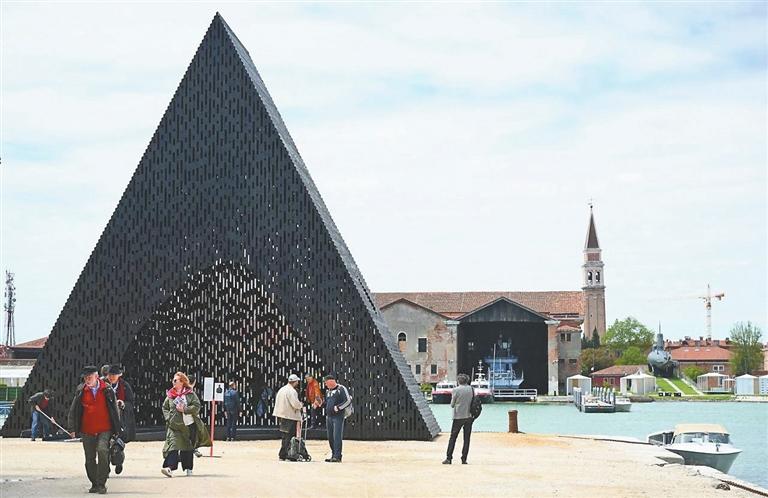

UNTIL recently, the Venice Architecture Biennale — arguably the world’s largest architecture exhibition — has drawn crowds for its star appeal. Big, established names from the realms of design and architecture have often been the main talking points, alongside pavilions that, for the most part, were all about the new, the innovative and the aesthetically pleasing. This year’s edition, its 18th, which opened to the public May 20 and is set to run until Nov. 26, feels drastically different. To start with, the average age of participants — 43 years old — is significantly younger than at previous editions, with only a few celebrity “starchitects” on the program, like British architect Norman Foster who presented a series of rapid-assembly buildings aimed to revolutionize post-disaster housing; and Ghanaian-British David Adjaye, who created a black timber pyramid for the Biennale and unveiled the design for India’s largest art and cultural center during the event. Then, Scottish Ghanaian architect and academic Lesley Lokko, who was called to curate the event under the title “Laboratory of the Future,” has brought the event’s focus firmly back to the duties of contemporary architecture, tackling issues like racism, the climate crisis and economic inequality. In doing so, she has delivered one of the most politically-engaged, environmentally-aware and inclusive Biennales in a long time — one where half of the practitioners hail from Africa or the African diaspora. Striving to minimize the environmental impact of the Biennale, Lokko urged the architects, artists and designers involved to adopt a “paper-thin” approach to their exhibits. Large-scale models and architectural displays are relatively hard to come by, and in their place are films, sculptures, drawings and even games (South Korea’s pavilion features a quiz show on the social political and economic issues surrounding climate change). Housed across three sites — the Giardini public gardens where countries present projects in a series of national pavilions; the Arsenale, Venice’s old shipbuilding yard and the city center — installations revolve around the themes of decolonization and decarbonization, while also expanding the notion of architecture to include art, performances and even activism. This apparent lack of architecture, in its most classic form at least, has bothered some. In a May 20 Facebook post titled “Venice Biennale Blues,” Zaha Hadid Architects’ principal, Patrik Schumacher, wrote that “the ‘Architecture’ Biennale is mislabeled and should stop laying claim to the title of architecture.” But in employing a wide variety of mediums, Lokko’s edition may actually be stretching the discipline’s reach in compelling new ways. The German pavilion, which is displaying construction waste produced by 2022’s Venice Art Biennale is a case in point. Here, as people explore the space, craftspeople work to repurpose the found materials, essentially turning the museum-like space into a dynamic workshop. Similarly, the Netherlands has replumbed its pavilion — a Biennale icon, designed by Gerrit Rietveld in 1953 — to collect rainwater. Switzerland has simply knocked down the wall dividing its pavilion from Venezuela’s in a project called “Neighbors,” which explores territorial relationships within the Giardini and the professional bond between the architects of the two buildings, the Swiss Bruno Giacometti, who designed the Swiss Pavilion and the Italian Carlo Scarpa, who was tasked with the Venezuelan one. Spain, meanwhile, has focused on food production with “Foodscapes,” a five-film audiovisual project accompanied by a recipe archive and a public program of conversations to investigate past and present food systems while exploring better, more sustainable ones for the years ahead. The British pavilion, too, feels more like an art show than an architecture display, with different artists showcasing objects or installations reflecting diasporic culture in the U.K. Among them is designer Mac Collins’ giant, futuristic domino tile — the game is played widely by British Caribbean communities inside pubs and public spaces across the U.K. — and an intimate series of domestic objects made from fabric, textile waste and aromatic blue Angolan soap, by artist Sandra Paulson.(SD-Agencies) |