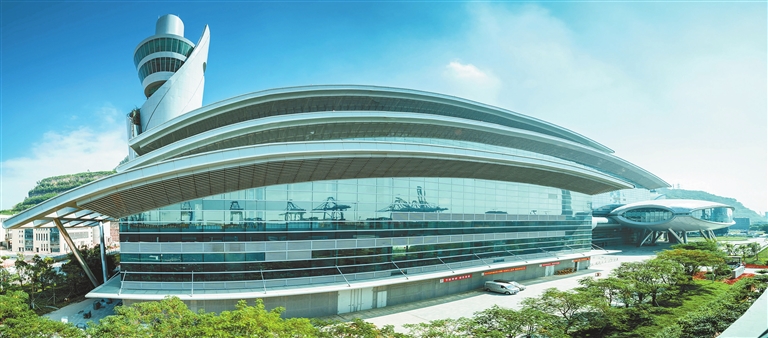

Zach Mills szdaily@126.com SEVENTY-TWO meters above Shenzhen’s coastline, a café offers visitors panoramic views of the Pearl River Estuary as ships drift by. But this is no ordinary café. It sits atop the chimney of a facility that processes over 2,600 tons of garbage every day – the Nanshan Energy Ecological Park, one of the world’s most technologically advanced waste-to-energy (WTE) plants. Placing a café atop a power plant is more than a novelty. It is a symbol of China’s broader environmental revolution. The country, once dubbed the “factory of the world” and grappling with the resulting pollution, is now deploying cutting-edge green technology nationwide. The Nanshan facility exemplifies this strategic shift, offering a sophisticated answer to one of the most pressing urban challenges: what should we do with our waste? As a cornerstone of Shenzhen’s circular economy vision, it proves that essential infrastructure doesn’t have to be hidden away but can instead become a source of community pride and environmental stewardship. Urban waste: A global challenge To understand the significance of a facility like the Nanshan Energy Ecological Park, one must first consider the grim alternative – landfills. Not only do they consume vast tracts of land near population centers, but they also breed pests, release foul odors, and threaten the environment. A primary danger is the contamination of soil and groundwater from leachate, a toxic liquid that percolates through decomposing waste. Landfills are a blight. While most people agree they are necessary, the sentiment is almost always “Not in My Back Yard” (NIMBY). This phenomenon has a troubling social justice dimension. Across the world, landfills are disproportionately sited near marginalized communities, offloading their environmental and health risks onto populations least able to mitigate them. Beyond localized risks, landfills pose a global threat through their methane emissions. This greenhouse gas is alarmingly potent. According to the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), methane is over 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide during its first 20 years in the atmosphere. The scale is immense. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports that municipal landfills were the third-largest source of human-related methane emissions in the United States in 2022, accounting for roughly 14.4% of the total. Fundamental flaws Modern landfills do attempt to mitigate harm, albeit imperfectly. Liners and collection systems seek to contain leachate, but the fundamental problem lies in a catastrophic lifespan mismatch. The protective liners are designed to last for a few decades, but environmental scientists warn that the waste they contain can remain a toxic threat for hundreds or even thousands of years Many modern landfills also attempt to capture the methane they produce, but the system has a fundamental design flaw. Unlike natural gas fields, which are sealed under solid rock, landfill gas must be extracted from an active, unsealed environment. A single landfill “cell” can take two to five years to fill. Because it must accept waste daily, it cannot be permanently capped until full. Instead, it is only covered with a thin layer of soil each night, allowing large quantities of methane to leak out before it can be captured. The resulting ineffectiveness is stark. During a cell’s active years, the capture system collects only about 41% of the methane. Even after being permanently capped, the rate only improves to 71%. Of the gas that is successfully captured, most is used to generate electricity, while the rest is simply burned off (flared). Ultimately, the system is so leaky that multiple studies estimate 30-50% of all methane from U.S. landfills escapes directly into the atmosphere. By contrast, neither leachate nor methane escapes the Nanshan facility. This level of containment is achieved through a completely different approach to waste management: thermal treatment in a closed-loop system. The WTE process Every day, sealed trucks haul municipal solid waste to the Nanshan facility. Inside a vast, subterranean bunker, grappling cranes continuously blend the waste into a homogenous mixture for optimal combustion. The bunker is kept under negative pressure, ensuring all odors are contained within. From there, the waste is fed onto moving grates and combusted at over 850°C (1562°F), a temperature that effectively destroys harmful organic compounds. The intense heat from this process boils water into high-pressure steam, driving turbines to generate electricity. Simultaneously, the hot flue gas is channeled into a comprehensive treatment system designed to produce emissions cleaner than the rigorous standards set by the European Union’s Industrial Emissions Directive. Before any gas is released from the chimney, it is scrubbed of pollutants in a multi-stage process that neutralizes acid gases, removes nitrogen oxides, and absorbs heavy metals like mercury. The final and most critical stage is the baghouse filter. This industrial system forces the entire gas stream through thousands of durable fabric bags, a technology analogous to HEPA filtration that captures over 99.9% of all fine particulate matter, or fly ash. The air leaving the chimney is so clean that real-time monitoring data is displayed publicly at the park’s entrance, demonstrating a level of transparency and performance that redefines what a power plant can be. From trash to turbines The Nanshan facility alone processes 950,000 tons of municipal solid waste annually as part of a revolutionary city-wide effort. According to Shenzhen’s “2024 Ecological Environment Status Report,” all municipal waste now undergoes incineration at the Nanshan facility and four similar parks. This makes Shenzhen one of China’s first megacities to eliminate landfilling – a landmark achievement in urban sustainability. From this waste, the Nanshan facility produces approximately 550 million kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity each year. To put that figure in perspective, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator shows that this is enough energy to power over 45,086 American homes for a year. The climate impact is equally significant. According to the facility, generating the same amount of energy with fossil fuel would release 220,000 metric tons of carbon emissions annually — the equivalent of taking 51,000 gasoline-powered cars off the road. A model for China and the world The facility’s success is the culmination of a decades-long effort rooted in strategic adoption, international cooperation, and domestic innovation. Shenzhen, long China’s experimental zone for economics and technology, began importing advanced WTE technology from Europe in the early 2000s. Over the next decade, local engineers mastered, adapted, and ultimately improved upon these designs, experimenting with new technological routes along the way. This model has been so successful it is now being scaled nationwide. According to national development plans, China aims to achieve a total municipal solid waste incineration capacity of 800,000 tons per day by the end of 2025. For perspective, that tonnage is roughly equivalent to the entire amount of municipal waste generated by the United States per day, based on a 2018 EPA report. Shenzhen Energy Environment (SEE) Co. Ltd., the company behind the Nanshan facility, has expanded its waste treatment operations nationwide. According to a 2024 company filing with the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, SEE had 42 operational solid waste plants in places such as Guangxi, Hubei, and Shandong at the end of 2024. Together, these plants have a combined daily treatment capacity of 50,515 tons of solid waste, and in 2024, they processed a total of 13.98 million tons. This includes a capacity of 7,565 tons per day for specific streams like kitchen waste, biomass, sludge, and construction materials. Looking ahead, SEE has an additional 16,905 tons of daily capacity in its pipeline from projects that are under construction or have been approved. These plants are a crucial component of China’s strategy to fulfill its commitments under the U.N. Paris Agreement. They contribute directly to the country’s “dual carbon goals” – reaching peak carbon emissions before 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. The model has also garnered significant international recognition. The Nanshan facility itself has earned the LEED Gold certification, while its sister plant, the Yantian Energy Ecological Park, was awarded the prestigious 2019 Paulson Prize for Sustainability. The prize committee cited the Yantian facility for its overall environmental impact, creativity, financing models, and improvements to quality of life. The committee called it a model for “balancing the need for clean energy and efficient waste management in a location that fits into any city or town,” making WTE a possibility for communities far beyond Shenzhen. The model’s global appeal is concrete. Following a visit to the Nanshan facility, Kazakhstan hired SEE to build a similar WTE plant in its capital. Redefining civic infrastructure Beyond its technology, the Shenzhen model’s true innovation is redefining civic infrastructure. The decision to make an industrial plant a beautiful public landmark is as revolutionary as its WTE process. This was the focus of the Paulson Prize, which celebrated the Yantian plant not just for its efficiency, but for serving the community with “landscaped grounds, public education spaces, and a visitor center for eco-tours.” This commitment to the public is set to expand. By the end of next year, the Nanshan plant will open an annex featuring a gym and a temperature-controlled swimming pool – all heated with recycled energy from the plant’s own generators. The Nanshan plant offers a tangible experience of what China calls “ecological civilization,” what the U.N. frames as “harmony with nature” and “sustainable cities,” and what others describe in their own terms — different words for humanity’s shared vision of a better future. It poses a quiet but powerful question: what if the infrastructure we depend on was not a problem to be hidden, but a source of pride, education, and human connection? |