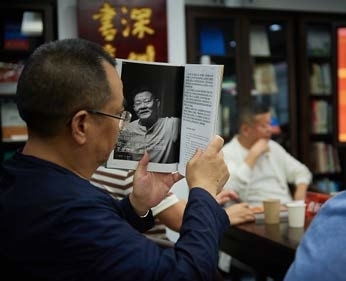

ON the 45th anniversary of the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, Book Capital magazine released a cover feature, “Shenzhen Ordinary People’s Writing Through 45 Years: The Language of a New Mass Cultural Movement in Shenzhen.” The issue traces the rise of grassroots writing around four keywords — pursuit, rooting, embrace, and reflection — and shows how ordinary voices have illuminated Shenzhen alongside its economic growth. Far beyond official narratives, the magazine highlights untold stories that capture the city’s vitality. From pursuit to rooting In 1984, factory worker Lin Jian’s “Late at Night, By the Sea, There Is a Man” marked Shenzhen’s early literary scene; two years later customs officer Liu Xihong’s “You Cannot Change Me” further voiced the city’s spirit. In 1990, 16‑year‑old Yu Xiu’s “Bloom During the Rainy Season,” tucked away for six years before publication, became a bestseller and symbolized the pulls that drew many to Shenzhen. As newcomers arrived, others put down roots. Security guards Li Yekang and Ye Er brought grassroots novels to the Chinese Writers’ Association, while community writers chronicled life across Shenzhen’s 696 neighborhoods — documenting workers’ endurance, women’s entrepreneurship and small traders’ fortunes and losses, forming the city’s literary DNA. Poet Guo Jinniu, once a construction worker and vendor, found recognition with his collection “Gone Home on Paper,” reaching audiences as far as the Rotterdam International Poetry Festival. Zhong Jiexia serialized a long novel online and collected city snapshots into “Poems of Shenzhen.” Second‑generation local Shi Xiaohan, winner of the 8th Top 10 Books of Shenzhen, says, “What I write may not always be about Shenzhen, but Shenzhen is everywhere in my words.” Building the city with words From migrant-worker poets to young local authors, diverse voices have shaped Shenzhen’s cultural texture. Critic Liao Lingpeng calls this trend “inclusive literature,” marked by openness and sharing. City slogans like “Build a city with literature” and “Write community chronicles” reflect a civic drive to record everyday history. Writers are seen as living biographies of the city: Xue Yiwei’s 12 short stories portray communities; Nan Zhaoxu measures the land on foot; Wang Guohua records neighborhood life. The internet has expanded reach — online works such as “Paradise Left, Shenzhen Right” and “Moments in Paradise” capture both the era’s rhythm and individuals’ quests for freedom and identity. “Linghu and Wuji,” a winner of the first Shenzhen Online Literature Contest for Realistic Works, notes how residents have gradually given the city its depth. New voices, future visions In December 2024, the first Shenzhen Reality‑themed Online Literature Awards honored works that caught the city’s breath and pulse. As one winner put it: “In Shenzhen, even fallen leaves in spring aren’t about death — they’re simply making way for new growth.” Science fiction has also risen: Bank clerk Hai Yan won a Hugo in 2023 for “The Time‑Space Painter”; Chen Qiufan balances tech work with novels on human‑machine ethics; even students like Xu Weixuan write speculative tales. These dual identities — workers by day, creators by night — reflect Shenzhen’s mix of practicality and imagination. A city written by its people Often seen as a hub of “efficiency, innovation, and GDP,” Book Capital argues Shenzhen is equally a city of stories. From factories to classrooms and online spaces, ordinary people have written its warmth, resilience, and hopes. Book Capital, a public‑interest cultural magazine under Shenzhen Publishing Group, aims to be “a cultural manual of the city,” weaving reading into urban life. As Shenzhen turns 45, the magazine concludes the city’s miracle is not only built in glass and steel but written — word by word — by ordinary hands. (Windy Shao) |