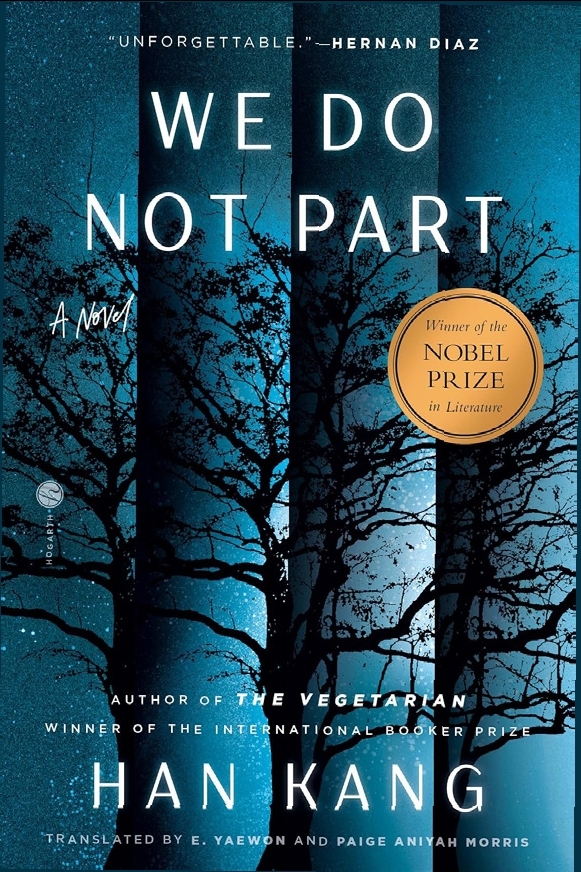

Han Kang, the recipient of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature and the first Korean author to win the prize, has returned with “We Do Not Part.” First published in Korean in 2021 and translated into English by Emily Yae Won and Paige Aniyah Morris this year, the book follows writer and protagonist Kyungha when her documentarist-turned-carpenter friend Inseon, undergoing emergency treatment for a hand injury, asks her for a favor: to travel to Inseon’s remote home on Jeju Island to feed her pet bird. Holed up in Inseon’s house during a dangerous winter, Kyungha finds herself haunted by her friend’s family history — a story of political violence, unresolved grief, and truth seeking. At the heart of the novel lies a narrative about the Bodo League massacre, a series of mass executions of alleged communist sympathizers that the South Korean government carried out in 1950. According to some estimates, up to 200,000 Koreans — some of them children — were killed. In the novel, the family members of Inseon’s mother were among those detained and murdered — a story that reveals itself slowly as a ghostly apparition of Inseon, upon meeting Kyungha in her house, provides her own narration. Han is no stranger to exploring the legacy of mass murder, having written about the 1980 Gwangju massacre in the novel “Human Acts,” which she considers to be of a “pair” with her latest book. Echoes of “Human Acts” linger throughout “We Do Not Part,” most notably in the fact that Han repeatedly declines to recount history in a conventional way. Stories of the massacre are filtered through multiple layers of telling — for instance, Inseon telling Kyungha the stories that her mother told her. The perspective shifts between Kyungha’s narration and Inseon’s storytelling, while the plot itself progresses non-chronologically through scenes of historical events, flashbacks showing the two women’s friendship, and the novel’s present-day narrative. “We Do Not Part” is unconcerned with reproducing reality. Instead, the book leads the reader through a narrative that, real or not, grasps at the story’s emotional truth. The novel’s dreamlike atmosphere dissipates in its third act, which pulls back from the book’s previous reality-bending style to give a more straightforward retelling of history. While this makes the story less immersive, the shift to a more direct account is arguably needed to drive home the horrific nature of the events described in the novel. The book returns to form in the final section, “Flame,” which closes the novel with its characteristic surrealism, imagery, and expressive prose. |