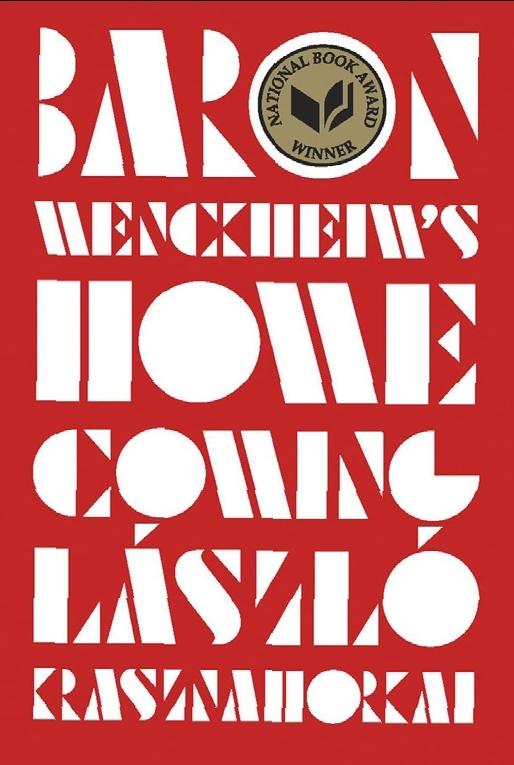

Author László Krasznahorkai won the Nobel Prize for Literature this year. Originally published in Hungarian in 2016 and translated by Ottilie Mulzet, the novel is set in a dilapidated provincial town in Hungary, a community rotting from within under the rule of a pompous, inept Mayor and his enforcers. Into this moral vacuum returns Baron Béla Wenckheim, the last scion of a noble family, who arrives from Buenos Aires in disgrace, fleeing gambling debts and carrying only a few coins. The town, however, buzzes with a different narrative. Whispers claim the Baron has returned with fabulous wealth to revitalize his ancestral home. This misunderstanding ignites a frenzy of greed and ambition. Bureaucrats, criminals, and ordinary citizens alike descend upon the Baron, each seeing him as their personal savior. While the Baron’s return acts as the catalyst, the novel’s true protagonist is the town itself — a technique echoing Krasznahorkai’s debut, “Sátántangó.” The narrative deliberately digresses, introducing a sprawling cast. A key figure is the Professor, a world-renowned moss expert who has abandoned his career to live in a shack. His life is violently interrupted by the arrival of a daughter he never knew, an event that bizarrely earns him the admiration of a local neo-Nazi biker gang. Characters like the Professor appear and vanish, underscoring the novel’s nonlinear, dissonant structure. Amid the chaos, the Baron is a tragic, spectral figure. His mind is deteriorating, and his sole purpose is to reunite with his childhood sweetheart, Marika. His failing memory renders his hometown both familiar and alien; he observes, “This was not the same town, and yet he was compelled to acknowledge that it was exactly the same, but it was as if somehow it had become a copy.” In a poignant, comedic moment, he fails to recognize Marika because she no longer matches the image preserved in his mind. As the truth about the Baron’s poverty emerges, initial excitement curdles into disillusionment and blame. The town’s moral decay is laid bare. Strangers mysteriously appear, and a biblical plague of frogs descends, amplifying the sense of impending doom. In the end, the worlds the philosopher, the baron, and other characters inhabit are slated to disappear in a wall of flame, an apocalypse that, as Krasznahorkai assures, is not just physical and actual, but also existential. This book may be a challenge for readers unused to endless sentences and unbroken paragraphs but worth the slog for its wealth of ideas. |