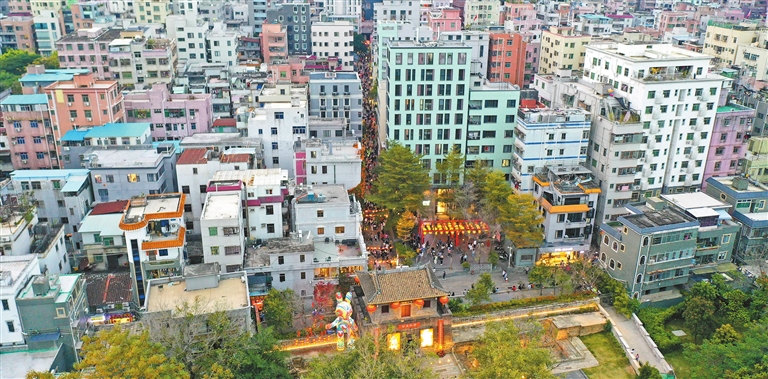

Sterling Platt SterlingPlatt@qq.com TO the casual observer — or the newly arrived expat — Shenzhen often feels like a city born yesterday, a sci-fi landscape of glass and steel. Yet, hidden behind the skyscrapers of Nanshan District lies a surprising predecessor to this modern metropolis: the 1,700-year-old Nantou Ancient City. Once the economic and political heart of the region, complete with defensive walls and temples, Nantou offers a stark contrast to the gleaming CBD just outside its gates. For years, Nantou was defined by the “handshake building” phenomenon. As Shenzhen’s population boomed over the last few decades, local landlords maximized their 10-by-10 meter plots by building upwards, creating 10-story rental towers so close together that neighbors could literally shake hands through the windows. These “urban villages” became labyrinths of narrow alleys, nesting between planned developments. By 2020, they accounted for roughly half of all residential space in the city. For many, places like Nantou represent the gritty, bustling engine room of Shenzhen’s success — crowded, convenient, and undeniably vibrant. However, charm often comes at a cost. Like many urban villages, Nantou suffered from poor infrastructure, a lack of sunlight, and safety concerns. In the past, the typical solution was simple: tear it down and build a park, large-scale residential development, or mall. A ‘living museum’ City planners, however, saw Nantou differently. They identified it as a “unique treasure” — a rare site that is both a walled ancient city and a modern urban village. It represents the full spectrum of local history, from its 1,700-year-old roots to the explosion of modern reform. The goal became clear: preserve that continuity rather than erasing it. This was easier said than done. Historical Nantou had become essentially invisible, with only 23 historic structures remaining — a mere 2% of the buildings — physically hidden behind the dense wall of handshake buildings. Planners argued that Nantou needed a new model. Instead of wholesale demolition, they re-envisioned the area as a “living museum.” The objective was to make the city’s layers — from ancient regional capital to migrant hub — legible and respected. In this new vision, the messy mix of ancient temples and dense tile-clad residential buildings would not be treated as a blight, but as the star attraction. Spatial reorganization and curation strategy Instead of wholesale demolition, the plan prescribed precise, small-scale interventions — strategic insertions, clearings, and connections to make historical layers legible and improve livability. A primary initiative was the implementation of a “differentiated design” for the street network. For the main north-south historical axis, the goal was to create a formal and orderly atmosphere. This was achieved by unifying the visual interface of ground-floor facades, specifically by requiring that modern buildings adjacent to heritage sites “coordinate with the style of the ancient buildings” in their materials and colors. Conversely, for the side alleys, the strategy was to amplify their unique existing identities based on their history or primary use. For example, the “Returning Home Alley,” the route for going to school, was made safer by moving chaotic overhead wires underground, improving lighting, standardizing pavement, and adding colorful murals and child-friendly street furniture. Revealing the hidden To make the ancient city visible again, planners employed a strategy of subtraction. By selectively removing modern buildings that blocked sightlines, they revealed 23 previously hidden historical structures and transformed seven key heritage nodes into curated public squares. The results are striking. At the South Gate, clearing the clutter re-established a dignified entrance plaza. At busy intersections like the Cross Street Center, ground floors were opened up to create multi-level spaces for people to sit and gather. Designers also carved out breathing room in the dense concrete jungle. By targeting unsound buildings for demolition, they created a network of “pocket oases” — micro-parks providing much-needed light and greenery. Simultaneously, underutilized structures were reprogrammed as “creative alleys,” injecting new economic energy into the area. Finally, the project tackled the unglamorous but essential work of keeping the neighborhood livable. A “Municipal Special Plan” overhauled long-neglected infrastructure. This included upgrading water supply and drainage systems, implementing rainwater and sewage diversion, and enhancing public safety by improving fire access routes and adding new fire hydrants. Most noticeably for residents and visitors, the chaotic tangle of overhead electrical and communication wires was finally buried underground, clearing the skyline. Through this careful curation, Nantou has evolved from a fossilized relic into a functional community, setting the stage for a dynamic interplay between the old and the new. Old and new While the street-level spatial strategy opened up Nantou, the architectural strategy required a granular, building-by-building approach. The project data tells a story of restraint: of the 1,043 existing buildings identified in the ancient city, planners removed only 121 structures (11.6%) to clear space for new public plazas and reveal sightlines to heritage sites. Crucially, the remaining 922 buildings were treated with a varied “light touch” rather than uniform renovation. The plan designated 619 buildings for simple facade updates, 159 for comprehensive renovation, and left 144 completely untouched, highlighting that the strategy was one of careful curation rather than a demolition derby. To manage this mix, the architectural design focused on the interplay between retained buildings and new insertions. A “differentiated strategy” was essential. For the legally protected heritage treasures — centuries-old temples and guild halls — the principle was one of utmost respect: “Repair the old as old.” Interventions here were minimal and meticulous, focusing strictly on structural stabilization and maintaining material authenticity rather than attempting to polish them. The restoration of the Guandi Temple, for instance, was handled with the care of an archaeological dig. Workers repaired traditional roof tiles and masonry using compatible mortar, aiming to ensure structural longevity without making the ancient structure look artificially “new.” This allows the original structure to serve as an authentic historical anchor. For the everyday shops, residences, and workshops that act as the living museum’s connective tissue, the principle was to “retain the spirit, not the object.” The Nantou Hybrid Building is the ultimate expression of this. Architects preserved the chaotic, tiled facade of the original building as a historical exhibit but gutted the interior to insert a sleek, modern core that meets contemporary needs, creating a direct fusion of past and present in a single structure. Finally, for recently built, low-quality structures, the mandate shifted to partial or full demolition and replacement with contemporary architecture. The new Tourist Service Center exemplifies this with a bold facade of glass bricks. It avoids mimicking the old, instead engaging in a deliberate interplay of contrast. It uses modern materials to frame the historic fabric around it, ensuring the new chapter in Nantou’s story is clearly written yet respectfully integrated. This tiered system — from the silent preservation of sacred relics to the bold contrast of new inserts — deliberately avoids the trap of creating a “fake antique” town. By ensuring every era is legible, the project has created a vibrant environment where history and modernity engage in a continuous dialogue. Successful preservation Ultimately, the Nantou regeneration project succeeded by redefining what preservation actually means. It proves that a city’s history isn’t found in “static relics” trapped behind glass, but in the dynamic layers of the streets themselves. Walking through Nantou today — perhaps holding a craft coffee in the shadow of a 1,700-year-old wall — it is clear that this experiment has worked. The planners have selectively woven together meticulous conservation and “adaptive reuse” to transform what was once a blighted maze into a walkable timeline. The result is a vibrant “living museum” where ancient structures, the dense “handshake buildings” of the economic miracle era, and modern facades stand side-by-side. Instead of being replaced, they coexist. It ensures Nantou remains a functional, lived-in neighborhood, telling the complete, layered story of the city we now call home. |