UNLIKE blockbusters that were huge successes at the box office, these films did not try to woo patrons. Rather, they were the efforts of those who tenaciously wanted an answer to questions that haunted them and our society. In this sense, these films are worthy of our attention.

Karamai

— a 356-minute documentary by Xu Xin

The film starts with a five-minute shot of a cemetery.

Known as the “12/8/94 Incident,” a devastating fire broke out in the Karamai Friendship Theater in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, killing 323 people, 288 of whom were schoolchildren. The cemetery is where they rest today. “Karamai,” which premiered at the 34th Hong Kong International Film Festival, brings back the memories.

In making the documentary, in which he interviews more than 60 relatives of the victims, Xu gained a deep understanding of the tragedy. He tries to convey this agony, shooting in black-and-white with no music or voice over throughout the film’s somber six-hour running time.

“Everybody keep quiet! Don’t move! Let the leaders go first!” was the instruction shouted out by one of the organizers when the fire broke out, as reported in the Far West China News.

Despite having escaped the fire unharmed, the government officials failed to call for help in time and unlock the exits of the theater. In the aftermath of the fire, a State investigation put 13 officials in jail and compensated families who had lost members.

“They think we can have another child, have an early retirement, and live a good life. They are wrong,” the interviewed parents said. “The wound never heals.”

Judge

— a 98-minute drama directed by Liu Jie

A prisoner on death row for stealing cars, a man who wants the prisoner’s kidney, and a traumatized judge whose marriage is falling apart — Liu Jie manages to weave these elements into his film “Judge,” which premiered at the Venice International Film Festival in 2009. The film has shown at the LA Film Festival, been nominated for awards at the Golden Horse Film Festival and won the FIPRESCI Prize at Miami International Film Festival.

Qiu Wu is on death row for stealing two cars, an appropriate sentence according to law. Coincidentally, the lead judge on the case just lost his daughter in a traffic accident involving a stolen car. An unexpected change in the law creates an opportunity for the car thief to avoid execution. Meanwhile, the convicted man is trying to donate one of his kidneys to a dying wealthy businessman to have his sentence reduced. While lobbying authorities, the businessman discovers he can be given the convict’s kidney only after his execution. With the new criminal law coming into effect on the day of the execution, the judge is facing a hard decision.

In theory, the judge is a hero because he sticks to the law; in reality he lives a poor alienated life with no friends. “Judge” is the latest film about the Chinese legal system, which is in constant improvement while still frequently questioned by the public. This is the second film by young director Liu Jie. His directorial debut, “Courthouse on Horseback” also focuses on the legal system.

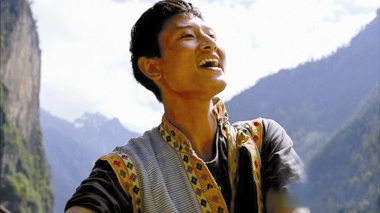

Deep in the Clouds

— a 98-minute drama directed by Liu Jie

The film won the Jury Grand Prix and Best Director awards at the 13th Shanghai International Film Festival.

Employing local actors speaking their ethnic Lisu language, the film is a present-day tale set in a remote village in southwestern China. Superstition still rules the villagers, who believe they are descended from the bears in the mountains and are strongly influenced by the pronouncements of the oldest man in the village, the centenarian Duoliba, who sits counting sweet corn to measure his remaining days.

Seven years ago, Duoliba’s son and elder grandson crossed the border into Myanmar to look for work and have not been heard of since. Considering them dead, Duoliba wants his younger grandson Dialu to marry his elder brother’s wife. Dialu actually loves the beautiful Jini, but she is under pressure from her father to marry a wealthy but drunken villager to secure her family’s future. While Dialu ponders whether to disobey his grandfather and go to Myanmar to find his father and brother, tension rises in the cash-strapped village, and are exacerbated by Duoliba’s refusal to bend to government pressure to be relocated elsewhere.

The film gathers its strength from the clashes between ethnic tradition and modern civilization, but more importantly, from the complexity of real life presented by a well woven story.

Piercing 1

— a 74-minute animation by Liu Jian

The film tells a contemporary story set during the recent financial crisis.

Zhang Xiaojun came from a poor rural area to a big city. He put himself through university and found a job in a shoe factory. In 2008, the financial crisis forced the closure of many factories. Zhang lost his job.

One day, a supermarket guard beats him up, mistaking him for a thief. In vain, he asks the supermarket manager for financial redress. His dearest wish is to return to his village to resume a simple farming life. Just before his departure, the police arrest him. The supermarket manager also has his problems. On a moonlit night, the storylines converge in a teahouse near the city ramparts.

Although overly bleak at times, “Piercing 1” creates a credible world where bribery, poverty and police brutality work in tandem and no good deed goes unpunished.

With an investment of only 100,000 yuan (US$15,000), this film, with its originality and high technical standards, points to the future of Chinese animation films. (Li Dan)

|