|

SINCE the beginning of the millennium, the works of international architects have sprung up like mushrooms in China’s cities.

These urban gurus not only brought their cutting-edge designs here, but also brought the whole world’s attention to what can be built in China. Constant global media coverage has portrayed China as an open stage for ambitious, innovative urban design, a reputation which initially pleased those who were commissioning the building, but later raised doubts and reflections of whether the country was being misused as a testing ground for maverick projects.

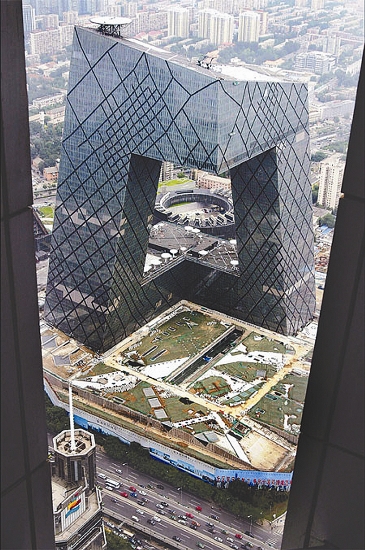

In Beijing, the National Stadium, otherwise known as the Bird’s Nest, was designed by Herzog & de Muron from Switzerland. The National Center for the Performing Arts was by French architect Paul Andreu and the landmark China Central Television Headquarters in the heart of the central business district is the work of Rem Koolhaas from the Netherlands, while the Beijing Capital International Airport was designed by Norman Foster from the United Kingdom.

What is happening in China is probably the largest urban construction movement in human history, a major motivation for first-class architects overseas.

Zaha Hadid, the world’s foremost female architect, drives it home when she compares China to “a perfect blank canvas” for architects with numerous opportunities.

Nevertheless, Peng Peikeng, a senior commentator at Qinghua University, is angered by the fact that some well-known foreign architects have obviously taken advantage of China’s eagerness to build dazzling modern cityscapes. He feels there have been too many architectural experiments here in recent years.

“The Pritzker Prize, architecture’s equivalent of Nobel Prize, is awarded to honor those who build works demonstrating ‘durability, utility, and beauty.’ This is widely accepted as the yardsticks for good building design. Sadly, many of these foreign architects’ works in China display none of these.”

Peng supports his criticism by pointing out that many of these designs would never be accepted by the architects’ home countries because they would have failed city planning concerns, stricter sustainable development demands and tighter budgets.

That is why they come to China, Peng says, a country that is currently open to almost anyone who can contribute “landmark buildings” in whatever form.

The architects are not solely to blame. More often than not, they are expected to deliver constructions whose only condition is to stand out from the crowd.

A recent plan for a new venue of China’s National Museum of Fine Arts, “the world’s largest art museum,” is the latest target for debate. It will be located near the National Stadium in Beijing’s Olympic Park and there are already worries that it may turn out to be another pair of “giant underpants,” the nickname for the asymmetrical twin legs of the CCTV Tower in the heart of the city’s Chaoyang District.

The desire for the new and eye-catching may be the result of historical baggage.

“China’s architectural style was greatly influenced by the Soviet Union for a long time, when the pursuit for charismatic individual design was curbed. It has now led to an outburst of fancy for the avant-garde, chic and novel, a desire made possible by the wealth accumulated during more than 20 years of economic reforms and opening up,” says Wu Liangyong, a senior architect and a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Chinese Academy of Engineering.

The desire to be different can lead to some odd experiments in the neighborhood.

Many domestic architects finger two landmark buildings as antithesis of the cases in point: One is the Jin Mao Tower in Shanghai and the other is the CCTV Tower in Beijing’s CBD. They regard these two landmarks as representing the best and worst in blending East with West, ancient and modern, and form and function.

Designed by SOM architects from Chicago, the Jin Mao skyscraper imitates an elegant Suzhou ancient tower and is highly functional at the same time, a fact lauded by experts and appreciated by Shanghai residents.

In contrast, design critics say the new CCTV building has “humiliated the Chinese” by its irreverent resemblance to a pair of boxer shorts, and its exorbitant price tag of 5 billion yuan (US$783.80 million).

“China is not so rich that we do not need to count the cost. We need real and practical solutions,” says Wu. “I hope none of my students will ever propose such irresponsible designs for a developing country.”

Some Chinese architects have heeded the clarion call to rediscover traditional architecture.

Liu Xiaodu of Urbanus Architects created an urban tulou (earth fortress) in Guangzhou, modeled after the circular fortified structures built by the Hakka people in Yongding, in neighboring Fujian Province.

His work successfully addressed how the old vernacular can provide inspiration for modern low-income housing that has a strong communal focus and improves the lives of migrants in urban enclaves.

(SD-Agencies)

|